A Context

1. Designated Historic Assets

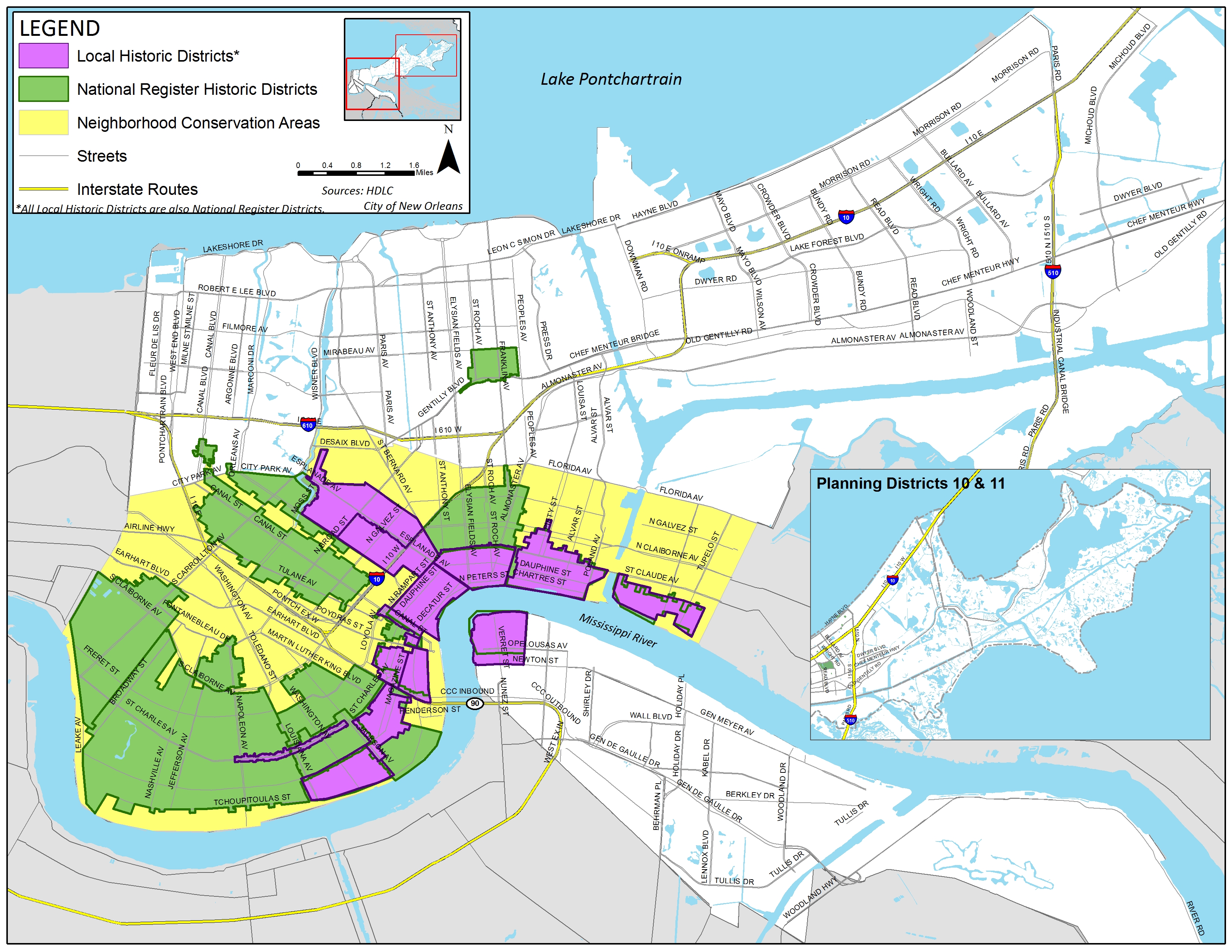

New Orleans’ historic resources include federally-designated districts and landmarks on the National Register of Historic Places, locally-designated historic landmarks and local historic districts, and neighborhoods outside historic districts that contain a wide variety of buildings dating from more than 50 years ago that are protected from demolition without a historic review because they lie within a Neighborhood Conservation District.

National Register Landmarks and Districts

As of June, 2009, New Orleans had over 140 landmarks and 19 districts listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The entire Vieux Carré (French Quarter) has been designated a National Historic Landmark. National Register districts and landmarks are designated by the US Department of the Interior and are administered by the State Historic Preservation Office in Baton Rouge. National Register designation is an honor—designation as a national landmark is the highest historic honor—but does not have any effect on a property owner’s right to modify or even demolish his or her property. There are approximately 37,000 buildings in the National Register Districts in New Orleans. After HurricaneKatrina, FEMA funded a very detailed historic survey with extensive photos of a number of New Orleans neighborhoods: Carrollton, Central City, Lower Garden District, Marigny, Parkview, Mid City, Tremé, and Esplanade Ridge. Expansion of this survey would provide New Orleans with an unparalleled resource.

HDLC’S BUILDING RATINGS GUIDE

|

|

BUILDINGS OF NATIONAL IMPORTANCE

These nationally important buildings include important works by architects having a national reputation, buildings or groups of buildings designated as National Historic Landmarks by the national Park Service, or unique examples illustrating American architectural developement.

BUILDINGS OF MAJOR ARCHITECTURAL IMPORTANCE

Buildings in this classification include outstanding examples of works by notable architects or builders; unique or exceptionally fine examples of a particular style or period when original details remain; buildings which make up an important, intact grouping or row; and noteworthy examples of construction

BUILDINGS OF ARCHITECTURAL OR HISTORICAL IMPORTANCE

This category includes buildings that are typical examples of architectural styles or types found in building building retains its original architectural details and makes a notable contribution to over-all character of a particular area of the city.

|

IMPORTANT BUILDINGS THAT HAVE BEEN ALTERED

This category includes important buildings that have had much of their exterior architectural details removed or covered, but still contribute to the overall character of an area.

BUILDINGS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO THE SCENE

These buildings generally date from the late nineteenth century or twentieth century and are typical examples of an architectural period or style.

UNRATED BUILDINGS

Buildings that have not been given a specifc architectural rating are generally twentieth century structures that have no real architectural value.

|

City-designated historic resources are administered by the Vieux Carré Commission (VCC)—which has jurisdiction over the French Quarter—and the Historic District Landmarks Commission, which has a 11-member commission focused on four downtown historic districts (CBD HDLC), and a 15-member commission with jurisdiction of all the other locally-designated historic districts (HDLC). These commissions also have jurisdiction over locally-designated landmarks. The Commissions review proposals in local historic districts that seek to change any part of the exterior of a building that is visible from a public way for historic appropriateness. They have a similar but more extensive regulatory power over landmark buildings, where any exterior surface—not just those visible from the public way—is subject to review. The Commissions also offer technical assistance to property owners and may issue citations for demolition by neglect (failure to maintain a building to such a degree that it is in danger of becoming uninhabitable). The historic fabric that comprises its historic districts has been professionally ranked according to significance. HDLC’s Buildings Rating Guide has six categories. The preservation plan for the Vieux Carré uses these same categories.

Locally-designated historic landmarks are typically located outside of local historic districts, except in the case where landmarks were designated before a local historic district was created. They include houses, neighborhoods, churches, cemeteries, public plazas, statues, monuments, college and university campuses, the St. Charles streetcar line, and two steamboats.1 A number of local landmarks are also national landmarks. There are 406 properties that are designated or nominated local historic landmarks as of mid-2009. Once a building is nominated, exterior changes are subject to review by the HDLC. The HDLC must prepare a study on the nominated buildings before they are formally designated.

In addition to the French Quarter, there are 14 local historic districts. Most local historic districts are also within National Register Districts, though there are a few cases where the borders of the local districts do not coincide with National Register Districts and include additional buildings.

Neighborhood conservation District

The Neighborhood Conservation District (NCD) encompasses an area generally south of I-610 on the East Bank, the historic districts on the West Bank, and all present and future National Register historic districts. The purposes of the NCD are: 1) to attempt to preserve buildings of historic or architectural value as defned by the HDLC or that contribute to overall neighborhood character; 2) to preserve and stabilize neighborhoods; 3) to promote redevelopment that contributes to historic character; 4) to discourage underutilization of property; 5) to advise the City Council as needed on issues related to the conservation of neighborhoods within the NCD. The NCD Committee (NCDC) is located within the Department of Safety and Permits and is

made up of fve community representatives from each City Council district and one representative each from the Ofce of Code Enforcement, the HDLC, the CPC and the Department of Health.

The primary role of the NCDC is to review demolition applications for properties within the NCD using as criteria: current condition; architectural signifcance; historic signifcance; urban design signifcance; neighborhood context; overall efect on the block face; proposed length of time a vacant site would remain undeveloped if demolition were granted; proposed plan for redevelopment; and public comment from neighbors, neighborhood associations or interested organizations. If a demolition permit is denied, the property owner cannot apply for another on the same building for a year, but can appeal to the City Council. Exemptions from review include: single story accessory structures not visible from the public way; demolition of less than 50 percent of the foor area and not including the front façade; structures within the jurisdiction of the HDLC or otherwise subject of demolition review; structures deemed to be in imminent danger of collapse. The Neighborhood Character Area Study prepared for this plan can be used to inform demolition decisions by the NCDC (see Appendix).

In other cities, Neighborhood Conservation Districts (NCDs) often include design guidelines based on an evaluation of neighborhood characteristics, so that additions, renovations and new development is reviewed for compatibility with existing neighborhood character. Design guidelines in NCDs are more lenient than in local historic districts and in many cases are developed with neighborhood participation, so that the level of regulation and type of regulation is acceptable to local property owners.

Illustrated Design guidelines

The HDLC received a federal Preserve America grant (to be matched with CDBG funds) in summer 2009 to develop new historic preservation design guidelines with illustrations. This publication will bring New Orleans up to date with comparable cities in providing guidance to owners of historic properties.

2. Stakeholders and Resources

In addition to the HDLC and VCC, there are several preservation organizations active in New Orleans.

Preservation Resource Center (RRC). The Preservation Resource Center is a non-profit founded in 1974 as an advocacy organization which has expanded into programs to rehabilitate historic houses. Its 45 staff members provide technical assistance, rebuilding assistance, advocacy on larger citywide preservation issues, and some financial assistance to community- based restoration efforts to encourage renovation of historic houses in New Orleans. PRC programs include:2

- Operation Comeback: Purchase, renovation, and resale of vacant historic properties since 1987, with heightened focus since Hurricane Katrina. A revolving fund provides continued resources for new projects, and the Adopt a House program seeks donations to support more housing rehabilitation. The program works with the City’s first time homeowner programs to provide affordable housing in rehabilitated historic properties.

- Rebuilding Together: An affiliate of a national organization, Rebuilding Together brings volunteers to New Orleans to assist in repair and renovation of homes for low- and moderate-income homeowners who are elderly, disabled, or first responders. From 2006 to mid-2009, 219 housing units have been repaired in New Orleans, with 38 in progress, using the labor of over 11,000 volunteers. The program works with neighborhood associations to identify eligible homeowners.

- Prince of Wales Building Crafts Apprentices program: Through the PRC, applicants who meet certain criteria (such as enrollment in Delgado Community College-Louisiana Technical College, or active membership in certain unions, or permanent residency in the Lower 9th Ward) can apply to receive stipends allowing them to attend the Prince of Wales program in England.

- Ethnic Heritage Preservation Program: The PRC developed this program with the African American Heritage Preservation Council through a partnership with Dillard University. A database of jazz-related sites is being developed and two plaques have been installed on buildings associated with jazz artists.

- Preservation Easement Program: Owners of historic properties can donate an easement on the property’s façade to the PRC in return for a tax donation. The easement gives the PRC the authority to approve or disapprove changes to the façade.

Established in 1950, the Louisiana Landmarks Society is the state’s oldest non-profit preservation organization, whose mission is to promote historic preservation through education, advocacy and operation of the Pitot House.

Landmarks rapidly defined preservation advocacy in New Orleans by leading the charge to preserve Gallier Hall in 1950 and defeat the proposed Riverfront Expressway a decade later. Landmarks’ most visible manifestation of its preservation principles is the historic c. 1799 Pitot House. Landmarks removed the Pitot House from the threat of demolition in 1964 when it acquired and relocated the structure 200 feet away. Landmarks’ preservation activities restored the c. 1799 Pitot House to its Creole West Indies colonial charm. Today, the Pitot House functions as Landmarks headquarters, as a venue for a variety of programs and events, and as a historic house museum open to the public.

Each year, Landmarks continues promoting historic preservation with the following events and activities:

- The New Orleans 9 Most Endangered List: Modeled on the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Most Endangered program, Louisiana Landmarks implemented its own list of the most endangered historic resources in New Orleans, beginning with the first list right before Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005. The goals for the program include: saving historic places, publicity for historic sites, advocacy for historic preservation, preservation education, and supporting proactive preservation efforts. A list of endangered places is an excellent tool for drawing attention to historic sites that may be threatened by demolition, neglect or bureaucracy.

- Lecture Series: Each year Louisiana Landmarks Society hosts a series of lectures on topics related to the preservation, culture, history and built environment of New Orleans, including the Martha Robinson lecture in May. Recent presentations include Roberta Brandes Gratz: We’re Still Here, Ya Bastards: How the People of New Orleans Rebuilt their City; the documentary film MisLEAD: America’s Secret Epidemic, presented by Dr. Howard Mielke, Ph.D., Department of Pharmacology, Tulane University School of Medicine; and, The Realities of Short-term rentals, with guest speaker Jay Brinkmann; and, The 50th Anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act and Transportation Act and the Second Battle of New Orleans, with guest speaker William E. Borah; and, The People and Places of the New Orleans Civil Rights Movement, presented by Dr. Raphael Cassimere, Jr., University of New Orleans Professor Emeritus of American Constitutional History and African American History.

- The Annual Louisiana Landmarks Society’s Awards for Excellence in Historic Preservation: honors architecture and construction projects completed in Orleans Parish (outside of the French Quarter) within a one year time span that represent outstanding examples of restoration or rehabilitation. Projects represent everything from modest shotguns and Creole cottages, to revived neighborhood theatres and markets, and a variety of public and private buildings. Projects honored meet criteria such as demonstrating that historic preservation could be a tool to revitalize older neighborhoods; show that historic preservation is “green” and sustainable; support the cultural and ethnic diversity of the preservation movement; are creative examples of saving a historic building; and, involve properties that utilized various federal or state tax incentive programs.

- Education programs: Each year, the Pitot House welcomes students from schools throughout the Greater New Orleans area. Field trips to historic houses help students appreciate Louisiana’s interesting history. Filled with beauty and mystery, historic buildings offer valuable insight and a connection with those who have contributed to the beautiful fabric of New Orleans.

- The Harnett T. Kane Award: Established by Harnett Kane (1910 – 1994), Louisiana Landmarks Society’s founding member and President, this prestigious award salutes those who have demonstrated lifetime contributions to preservation. An impressive list of preservation luminaries have been honored, with the first award given in 1968.

TABLE 6.1: SOURCE: LOUISIANA DEPARTMENT OF CULTURE, RECREATION AND TOURISM. HTTP://WWW.CRT.STATE.LA.US/HP/TAXCREDIT09P.ASPX. RETRIEVED AUGUST 2009.

| LOUISIANA TAX INCENTIVES PROGRAM QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE |

| |

FEDERAL HISTORIC REHABILITATION TAX CREDIT

|

LOUISIANA STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION TAX CREDIT

|

LOUISIANA STATE RESIDENTIAL REHABILITATION TAX CREDIT

|

| Purpose |

Encourage the preservation of historic

buildings through incentives to support

the rehabilitation of historic and other

older buildings

|

Encourages the preservation of historic

buildings through incentives to support

the rehabilitation of historic and older

buildings |

Encourage taxpayers to preserve and

improve their homes by offering a tax

credit on rehabilitation costs |

| Eligibility |

Income producing property individually

listed on the National Register (NR) or a

contributing element within a National

Register Historic District |

Income producing property that is a

contributing element within a Downtown

Development District or Cultural District

of Historic Preservation |

An owner occupied building that is a

contributing element to a NR District,

a locally designated historic district, a

Main Street District, a Cultural District,

or a DDD; a residential structure that is

listed or is eligible for listing on the NR;

or a vacant and blighted building at least

50 years old |

| % of Credit |

20% of construction costs and fees

GO Zone–26% for costs incurred from

August 28, 2005 through December 31,

2009 credit |

25% |

25% credit = AGI less than or equal to

$50,000.

20% credit = AGI $50,001—$75,000.

15% credit = AGI $75,001—$100,000.

10% credit = AGI $100,001 plus. (Avail-

able only for vacant and blighted resi-

dential buildings at least 50 years-old. |

Minimum

Expenditure |

The rehabilitation must exceed the

adjusted basis of the building. If adjusted

basis is less than $5,000, the rehabilita-

tion cost must be at least $5,000 |

$10,000 |

$20,000 |

| Credit Cap |

None |

$5 million per taxpayer within a particu-

lar DDD |

$25,000 per structure |

| Application |

Submitted to DHP and forwarded to NPS

with recommendation. Part 1 certifies

the building as historic. Part 2 describes

the proposed rehabilitation. Part 3 is final

certification of completed work |

Submitted to DHP. Part 1 certifies the

building as historic. Part 2 describes the

proposed rehabilitation. Part 3 is final

certification of completed work |

Preliminary Application—A establish

initial eligibility. Proposed Rehabilitation

Application—B determines if the

proposed rehabilitation is consistent

with the Standards. Certificate of

Completion—C is the final certification |

| Fees |

Initial fee requested by NPS of $250 with

Part 2; final fee is scaled to the size of

the rehabilitation |

$250 with Part 2 |

$250 with Proposed Rehabilitation

Application—B |

Program

Standards |

Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for

Rehabilitation |

Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for

Rehabilitation |

Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for

Rehabilitation |

Taking

the

Credit |

Credit is claimed for the year the project

is completed and has received an

approved Part 3. Unused Credit can be

carried back one year and forward for

20 years |

Credit is claimed for the year the project

is completed and has received an ap-

proved Part 3. Any unused credit may be

carried forward for up to 5 years. This

credit may be sold to a third party |

The tax credit is divided into 5 equal

portions, with the first portion being used

in the taxable year of the completion

date, and the remaining portions used

once a year for the next four years. If the

full credit for one year cannot be taken,

the owner will receive that amount as

a refund |

| Recapture |

If the owner sells the building within 5

years of the rehabilitation, he loses 20%

of the earned credit for each year short

of the full 5 years |

If the owner sells the building within 5

years of the rehabilitation, he loses 20%

of the earned credit for each year short

of the full 5 years |

If the building is sold during the five-year

credit period, all unused credit will im-

mediately become void |

| Phone: (225) 342-8160 Website: www.louisianahp.org |

|

|

|

The national main Streets pro-

gram provides resources to assist

communities in revitalizing historic

commercial districts.

Main Streets. Main Street programs, mentioned earlier in Chapter 5—Neighborhoods and Housing, were first developed to revitalize historic commercial districts and their program structure continues to serve as a strong foundation for preservation of historic commercial areas

The Green Project. The Green Project is a nonprofit organization that operates a warehouse store which resells high quality salvaged building material, much of which comes from historic structures that have been deconstructed rather than demolished.3

There is significant potential for

expanding heritage tourism activity

into historic areas of the city that

currently do not benefit from the

tourist trade.

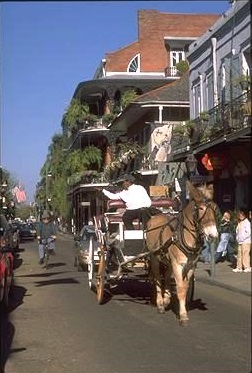

Tourism. While some of the city’s tourism promotion efforts capitalize on the city’s historic character and image, and there are a few tours of historic sites and districts offered by guide services, many New Orleanians see historic preservation as focused on the more traditional tourist areas of the city, particularly the French Quarter and the Garden District. However, there is significant potential for expanding tourism activity into some of the other historic areas of the city, which could lengthen the visitors’ stay,

and would benefit residents and neighborhood-serving restaurants and businesses as well as visitors.

Cultural preservation linked to historic preservation. The African American community tends to be less active in preservation organizations and initiatives, though many of New Orleans’ historic buildings were constructed and inhabited by the city’s African American working class. Moreover, these historic neighborhoods are the birthplaces of jazz (Tremé and others) and cultural traditions that are integral to New Orleans identity.

3. Historic Buildings

The ambiance created by the ensemble of historic buildings in neighborhoods—rather than monumental public buildings—is what attracts many people to New Orleans. Much of this vernacular historic housing in New Orleans was built for working people and for residents of modest means. Building rehabilitation practices mandated by historic district regulations are perceived as expensive and a barrier to historic renovation by low and moderate income owners. For developers and landlords, the gap between renovation costs and market sales or rental rates can be a deterrent, adding to the potential for continued disinvestment in some neighborhoods with historic building stock or, alternatively, rehabilitated buildings become unaffordable to the workforce for whom they were originally intended. Over time, the socioeconomic diversity of entire neighborhoods—and integral part of the “historic character” that so many New Orleanians seek to preserve—is eroded.

In 2008, Louisiana Act 431 created the Magnolia Street Residential Neighborhood Enhancement Program, within the Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism. The Magnolia Street program, which is modeled after a successful program in Pennsylvania, is similar to the Louisiana Main Street Program. Magnolia Street helps residential districts near a Main Street district implement a revitalization strategy. The program will provide residential reinvestment grants for infrastructure and structural improvements, such as streets, street lights, trees, exteriors of buildings, and sidewalks. The program will also provide an assessment of educational and recreational opportunities and facilities within an area, as well as provide grants to market and promote urban residential living and promoting home ownership within the residential areas. The program is being stewarded by the state Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism and is still in the process of getting started.4

Like many other older cities, New Orleans has a number of historic institutional buildings that will need to find new uses, many in the middle of residential neighborhoods. These buildings contribute to the historic character of their surroundings. The recent School Facilities Master Plan notes that: “some older school buildings will no longer be practical for use as educational facilities,” and recommends that they be “evaluated for their historic qualities and preserved and/ or adaptively reused for housing, offices, or other community uses.” Schools, churches, convents, and similar historic assets have found new life around the country (and in New Orleans) as housing, arts centers, business incubators and other modern uses.

Like many other older cities, New Orleans has a number of historic institutional buildings that will need to find new uses, many in the middle of residential neighborhoods. These buildings contribute to the historic character of their surroundings. The recent School Facilities Master Plan notes that: “some older school buildings will no longer be practical for use as educational facilities,” and recommends that they be “evaluated for their historic qualities and preserved and/ or adaptively reused for housing, offices, or other community uses.” Schools, churches, convents, and similar historic assets have found new life around the country (and in New Orleans) as housing, arts centers, business incubators and other modern uses.

The maritime industrial heritage of New Orleans is reflected in many historic structures on the riverfront and in its numerous historic warehouse and factory buildings. However, many are currently outmoded for modern industrial purposes and vacant or underutilized. The Warehouse District, where many historic warehouse buildings have been converted to artist studios, galleries, offices, restaurants, and housing, provides one precedent for adaptive reuse of industrial structures.

4. TWENTIETH CENTURY ARCHITECTURE

New Orleanians’ sense of historic identity is linked to the remaining 18th and 19th-century buildings in so many neighborhoods. However, buildings over 50 years old are generally considered candidates for historic preservation status. In addition to buildings from the first half of the twentieth century, such as the Art Deco Charity Hospital building, New Orleans also has examples of Modernist and Mid-Century architecture and neighborhood design, whose preservation value should be evaluated, including City Hall, several mid-century schools, office buildings and single-family homes. The architectural community has tended to be the strongest advocate for preserving mid-century buildings.

5. INTEGRATING CONTEMPORARY WITH TRADITIONAL ARCHITECTURE

Like many American cities with important historic building stock and a strong preservationist community, New Orleans has yet to develop the easy integration of contemporary and historic architecture that is more often found in Europe. Development of a set of guidelines for compatible contemporary design is needed to assist property owners and developers. Guidelines and criteria for evaluation would encourage more developers to use architects rather than engineers to design new buildings within historic contexts.

1 For a complete list of designated and nominated landmarks, visit http://cityofno.com/pg-99-28-landmarks.aspx.

2 www.thegreenproject.org

3 http://senate.legis.louisiana.gov/Gray/Topics/2008/julynewsletter.pdf

B What The Public Said

Previous plans for New Orleans—particularly the Unified New Orleans (UNOP) and Neighborhood Rebuilding Plans (Lambert) plans—placed top priority on preserving the overall character of neighborhoods and eliminating blight. Many individual plans expressed residents’ desire to ensure renovation of historic structures wherever possible (though demolition for reasons of health and public safety was also a high priority). Preserving New Orleans’ arts and cultural heritage and the socio-cultural diversity neighborhoods were frequently mentioned in these plans.

During the Master Plan process, public attention focused particularly on the following historic preservation concerns:

- Adopt a more holistic view of preservation as not just the renovation of physical structures but also the restoration of social and cultural heritage.

- Move away from a “museum-ification” and the “curatorial” approach to preservation and towards a more useful, functional, “living, breathing” form of preservation.

- Expand preservation initiatives to include social and cultural heritage.

- Preserve the overall historic character of neighborhoods, including their mix of uses, walkability, density, scale, architectural styles, and diversity of housing types.

- Preserve the character of streets and public spaces, including tree canopies, benches, landscaping, and both formal and informal gathering places.

- Encourage historic preservation throughout the city, not only in tourist-oriented areas

- Encourage the preservation of artisan skills and trades.