Overview

Chapter Overview

Introduction

Findings

- There has been a significant increase in the number of active neighborhood organizations since Hurricane Katrina and they have played a leadership role in initiating the city’s recovery.

- There is a wide divergence among different neighborhoods in the structure, breadth of membership, and other qualities that characterize community-serving organizations. As a result, some neighborhoods are more able than others to insure that all elements of the community (home-owners, renters, retailers, and others) participate in decisions that affect the neighborhood, initiate neighborhood plans, work with developers to revise proposals, and help shape land use decisions and other policies that affect qualityof life. A system of district wide councils that serve as an organization of community organizations in each district can “raise the bar” for all neighborhoods by assisting in capacity building; providing a forum for organizations to discuss common issues; initiating citywide conversations among multiple neighborhoods; providing a structure for working with developers and others to shape development projects, plans, and other land use decisions that enhance the quality and character of neighborhoods and meet essential tests of feasibility; and similar tasks.

- A more formal and effective neighborhood participation system that addresses the needs of all neighborhoods has been under discussion for over a decade.

Challenges

- Providing publicly-accessible information on city agencies, processes, and project proposals

- Enhancing capacity, where needed, among residents and among community-based organizations

- Providing technical support to neighborhoods and other communities to address issues of particular interest to individual neighborhoods upon adequate funding

- Creating a forum that brings together residents (owners and renters) and other members of the community in each district (business owners, property owners, institutions) to work together to resolve neighborhood issues and jointly advocate for neighborhood interests

- Providing a regular, meaningful, and accessible structure for community input into public decisions

- Increasing the transparency and predictability of public decision-making processes

- Creating a system that works for neighborhoods as well as businesses and project proponents

- Providing a streamlined, objective and predictable permitting process for proposed projects

- Finding a mechanism to facilitate participation by communities of interest

Acronyms

|

|

Acronyms used within this chapter:

|

| BGR |

Bureau of Government Research

|

DDD |

Downtown Development District

|

| CAO |

Chief Administrative Officer

|

DHH |

Department of Health and Hospitals |

| CBNO |

Committee for a Better New Orleans

|

E-COW |

Electronic Community Orientation Workshop

|

| CDBG |

Community Development Block Grant

|

LISC |

Local Initiatives Support Corporation

|

| CIP |

Capital Improvement Program

|

NEPA |

National Environmental Protection Act

|

| CPC |

City Planning Commission

|

NPN |

Neighborhoods Partnership Network

|

| NPP |

Neighborhood Participation Program

|

RTA |

New Orleans Regional Transit Authority

|

| D-CDBG |

Disaster Community Development Block Grant

|

UNOP |

Unified New Orleans Plan

|

A Introduction

T

th final element in the Master Plan focuses on specific activities and tools that can help ensure the implementation of the Plan and on making the Master Plan a living plan used by city government and its partners in the public, private and nonprofit sectors. This includes discussion of the City’s planning process for the capital improvement program, for which the City Planning Commission has responsibility.

The Capital Improvement Program (CIP) and the Annual Capital Budget and the “Force of Law”

The city government’s 5-year Capital Improvement Program and the annual capital budget must be consistent with the goals, policies, and strategies in one or more of the Master Plan’s elements. For example, capital improvement projects that involve acquisition of land for parks or transportation rights of way, improvements to community centers, or city investments in capital improvements funded by other entities must be consistent with the Master Plan. If a city department proposes a project for the capital improvement program, that project must further, or at a minimum not interfere with, the goals, policies and strategies in the various elements of the Master Plan. Similarly, the annual budget must not contain projects that interfere with the goals, policies, and strategies of the Master Plan. However, if a capital project is recommended in the Master Plan, the City is not obligated to fund that capital improvement. The City may also fund capital projects that are not in the Master Plan, as long as they are consistent with the Master Plan. The City Planning Commission has a process to certify consistency with the Master Plan for all projects proposed for inclusion in the CIP and the annual capital budget.

Structures Needed for Implementation

Adequate staffing and resources for the City Planning Commission to implement the Master Plan in partnership with other city agencies and governmental groups, citizens, the development and business community, educational and medical institutions, and other nonprofits

Organization and systems to support the City Planning Commission’s role in the City’s capital improvement planning process

Reports on a regular basis to the public and elected officials on progress in implementing the plan as well as updates and revisions to the Master Plan

A citywide system for government property maintenance and management

Improved internal and external accountability, including through an online public data warehouse (NOLAStat)

Working with the State and Federal Governments

This section of the plan also discusses how the Master Plan can help city government in its relationships with the state and federal governments. The Master Plan itself and the implementation of the Plan can play a crucial role in city government’s message to the federal and state governments. Federal commitments to infrastructure financing and to encouraging green industries and jobs all align with the goals of this plan. Close collaboration with state and federal legislative delegations,

as well as directly with the executive, will play a central role in the successful implementation of New Orleans’ Master Plan—as it does in the success of all older U.S. cities. The Plan’s extensive neighborhood participation process brings great legitimacy to the consensus on goals and policies in the future. Representatives of diverse interest, from elected officials to business leaders to residents, aligned around the same message can have a powerful effect in bringing local concerns into decisions by the state and federal governments.

B Recommendations

A recommendations Summary linking goals, strategies and actions appears below and is followed by one or more early-action items under the heading Getting Started. The Narrative follows, providing a

detailed description of how the strategies and actions further the goals. Background and existing conditions discussion to inform understanding of the goals, policies, strategies and actions are included in Volume 3, Chapter 16.

Summary

Next Five Years 2016-2021

2016-2021

| Goal |

Strategy |

Actions |

| How | Who | When | Resources |

|---|

| 1. A culture of planning requiring participation in

and approval of all planning that affects the city’s welfare

| 1.A. Position the CPC to take the lead in promoting the city’s interest in creating a quality urban environment from all development projects.

| 1. Provide the planning commission with the staffing and other resources necessary to implement the Master Plan |

Mayor’s office; City Council; CPC |

First five years |

General fund; federal funds |

| 2. Create a system in which all stakeholders work with project proponents and the city to resolve differences and create successful development outcomes |

CPC through the Neighborhood Participation Program |

First five years |

Staff time; Grants |

| 3. Create partnerships with the city’s educational and other institutions |

CPC; educational institutions; medical institutions |

First five years |

Staff time; grants |

| 4. Convene a cross-agency Master Plan Implementation Committee at least three times a year. |

CPC |

First five years |

Staff time |

|

1.B. Develop staffing expertise within the city regulatory and planning review agencies and departments of city government as to issues of design review

| 1. Require commissioners for HDLC, VCC, CPC and BZA to undergo training on matters of urban design |

HDLC, VCC, CPC and BZA |

First five years |

Departmental budgets, commissioner time |

| 2. Enhanced coordination between the CPC, planning staff, community development programs, and other entities that affect the city’s physical

development

| 2.A. Reorganize planning and zoning activities within city government to create a closer relationship between the CPC and implementing agencies

| 1. Create an interagency group focusing on proactive planning |

CPC; CAO; Senior leadership |

First five years |

Staff time |

| 2. Review the role and position of the CPC in relation to implementation agencies such as Community Development and NORA |

CPC; Mayor’s Office |

Medium-term |

Staff time |

| 3. Consultation of the Master Plan in making city decisions at multiple levels | 3.A. Make the Master Plan a living document

| 1. Review the plan every five years, as required |

CPC |

First five years |

Staff time; grants |

| 2. Update the Master Plan more thoroughly at least every 20 years |

City Council; CPC |

First five years |

Staff time |

| 3. Review progress on the Plan in an annual City Planning Commission meeting and an annual City Council meeting |

City Council; CPC |

First five years |

Staff time |

| 4. Use the Plan annually in preparing and approving departmental work plans, and the City’s operational budget, as well as its capital improvement program and capital budget |

Mayor’s office and agencies; CAO’s office and agencies |

First five years |

Staff time |

| 5. Use the plan in preparing and approving One-Year and Five-Year HUD Consolidated Plan documents |

OCD |

First five years |

Staff time |

| 6. Make multiple Planning Commission staff members into the Commission’s experts on the Master Plan |

CPC |

First five years |

Staff time |

| 7. Collaborate more closely with the CAO’s office on the CIP |

CPC; CAO |

First five years |

Staff time |

| 8. Update the Master Plan more thoroughly at least every 20 years |

CPC |

Long-term |

Staff time |

| 4. Capital improvement plan and capital budget consistent with the Master Plan | 4.A. Ensure capital improvement processes are linked to the Master Plan

| 1. Further refine the system to certify that capital improvement projects and any other public projects are in compliance with the Master Plan |

CPC |

First five years |

Staff time |

| 2. Maintain the City Planning Commission as the entity that certifies compliance with the Master Plan |

CPC |

First five years |

Staff time |

| 3. Through the zoning ordinance, evaluate large private projects for compliance with the Master Plan |

CPC |

First five years |

Staff time |

| 4. Continue publishing regular reports on the progress of capital budget projects |

CAO’s Office |

First five years |

Staff time |

| 5. Citywide system for government property maintenance and management | 5.A. Plan for maintenance, repair and replacement of assets

| 1. Make it a very high priority to establish an asset management system |

CAO’s office |

First five years |

General fund |

| 2. Create an interagency maintenance plan for stormwater management and green infrastructure assets |

CAO, S&WB, Parks and Parkways, NORA, public park administrators |

First five years |

General fund, federal grants |

| 6. Improved internal and external accountability | 6.A. Make transparency and communications an integral part of government operations

| 1. Create a performance measurement system and information warehouse for city employees and to share with the public |

CAO’s office |

First five years |

Grant for setup; general fund and federal funds for operation |

| 2. Continue to enhance the city’s E-government capacity |

Mayor; CAO; ITI |

First five years |

Staff time |

| 3. Provide effective and meaningful access to information about municipal activities |

Mayor; CAO; ITI |

First five years |

Staff time |

|

6.B. Focus on more consistent and effective enforcement of municipal laws and regulations

| 1. Provide the tools, training and funding needed for effective enforcement of the City’s laws and regulations |

Mayor; CAO; line enforcement agencies |

First five years |

General fund; grants; federal funds |

| 2. Improve the Neighborhood Engagement Office and the 311 system to report back to citizens on enforcement actions |

Mayor; Office of Public Advocacy; 311 |

First five years |

Staff time |

| 3. Give “customer training” to staff who deal with the public and make the quality of interactions with the public part of employee reviews |

CAO’s office |

First five years |

Grants; Staff time |

| 7. More tax revenue for the general fund and an improved fiscal situation | 7.A. Seek opportunities to increase municipal revenues and resources for services, programs, and facilities over the long term

| 1. Recruit chain retail to serve New Orleans residents and increase the tax base |

NORA; Economic Development, NOLABA; CPC; regulatory strategy |

First five years |

Staff time |

| 2. Commission a study of how New Orleans can strengthen its fiscal position |

Finance Department |

First five years |

General fund |

| 3. Regularly review the fees generated by City departments to more fully offset the staff time and resources that are necessary to process and review applications |

CAO |

Regularly |

Staff time |

Getting Started

These items are short-term actions that can be undertaken with relatively little expenditure and will help lay the groundwork for the longer-term actions that follow.

- Organize a cross-agency Master Plan implementation committee.

- Work with the CAO’s office to further refine systems for use of the Master Plan in capital planning.

Narrative

Below is a more detailed narrative of the various goals, strategies and actions highlighted in the “Summary” chart.

1.THE POLITICAL FRAMEWORK

The City of New Orleans operates within a framework of state and federal legislation, policies, programs, and developments. It can do little to directly control the actions of state and federal actors. Federal funds and programs come with requirements. State and federal development projects in the city are exempt from zoning. Special districts created by the state pepper the city, and the state controls some aspects of the City’s ability to raise revenue. Although the Master Plan does not directly govern these capital investments made by the state or federal governments, they typically will consult with local government to make projects consistent with the Master Plan.

It is the City’s responsibility to work effectively with both state and federal governments to protect and enhance citywide and neighborhood interests. The City knows the reality on the ground and must play an essential role in guiding state and federal investment. The Master Plan itself and the implementation of the Plan can play a crucial role in city government’s message to the federal and state governments. The Plan’s extensive neighborhood-participation process brings great legitimacy to the consensus on goals and policies for the future.

The Master Plan goals and policies provide the framework for consensus policies and alignment of interests:

- The City can stake a claim to federal resources, not just because of its past, but because of what it can be in the future. New Orleans’ unique contributions to American culture combined with post-Hurricane Katrina rebuilding needs have been the main threads of the New Orleans story since 2005. This story has served as the foundation of requests for federal assistance. The City’s Master Plan opens up strategies for a long-term future of economic growth linked with sustainability and enhanced livability. Federal commitments to infrastructure financing, and to encouraging green industries and jobs all align with the priorities and goals of the Master Plan.

- City housing policy can shape state decisions about affordable housing investments. In the past, the state has often assigned low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC) to projects with an income mix, design character, and location that the City ends up protesting after the fact. Similarly, the City has served as a pass-through for federal housing entitlement funds by sending out a call for proposed projects, rather than working closely with housing advocates and developers to create the best projects possible. The City is further developing proactive housing policies based on New Orleans actual housing needs and a detailed understanding of sub local markets and physical character, so that LIHTC and other housing subsidies can be applied in ways that enhance neighborhoods. With clear policy guidance based on evidence of housing need and the support of a diverse working group, City staff can work effectively with state agencies to make sure that New Orleans benefits.

- The City can shape the physical character of major state and federal investments, despite its limited regulatory authority. The CPC’s responsibility for the physical development of the city makes it the logical leader in ensuring that major investments and developments, such as the LSU Medical Center and VA Hospital, enhance the physical and social character of the city, as well as contributing jobs and economic benefits.

Close collaboration with state and federal legislative delegations, as well as directly with the executive, will play a central role in the success of New Orleans’ Master Plan—as it does in the success of all olderU.S. cities. Because both state and federal programs and processes have their own bureaucratic and legislative rigidities, the City may need to be persistent and focused in gaining a hearing for its interests. Representatives of diverse interests, from elected officials to business leaders to residents, aligned around the same message can have a powerful effect in bringing local concerns into decisions by the state and federal governments.

2.THE FINANCIAL AND FISCAL FRAMEWORK

As a 20-year plan, the Master Plan includes many recommendations and strategies. After Hurricane Katrina, the city and the region received millions in recovery dollars and new investment. Now that the disaster-related funds and incentives have been spent, the City will need to make the most of existing revenue sources, generate new sources, and, at the same time, make an effective appeal on the state and federal levels for continued funding to achieve many of this plan’s goals.

- Cost savings from operating efficiencies must continue to be evaluated. Effective and efficient city government and use of resources can be promoted through establishment of a data-based performance-measurement system that would help city leaders identify how to make city government work better. In addition, Master Plan recommendations for coordinated and proactive planning can ensure that the city knows what it wants to do with entitlement funding (CDBG, HOME, and so on) it receives from the federal government, as well as federal transportation funding allocations, and does not allow funds to go unspent.

- The city needs to invest in adequate staff to help it win discretionary funding from government and foundations.

- On the federal level, New Orleans, because of its experience, has the opportunity to take a leadership role in a coalition of cities that will be affected by climate change. Cities like Miami, New York, Boston, and others are at risk, just like New Orleans.

- New Orleans property owners have shown that they are willing to vote for bonds to pay for street improvements and millages for libraries. Bonds, water and sewer rate increases, and similar strategies will have to be considered as part of the funding mix.

- User fees and betterment fees for certain services or improvements can help fund them and also promote desired actions. For example, many communities charge fees for removing more than one bag of trash a week as a way to fund services and to reduce solid waste. Approximately 1,600 U.S. jurisdictions have created stormwater utilities as a means of shifting a portion of drainage and sewerage costs to a user pays model.

- Incentives, such as tax-increment financing, can help attract private investment to desired locations.

2.15.1 A culture of planning requiring participation in

and approval of all planning that affects the city’s welfare

2.15.1.A 1.A. Position the CPC to take the lead in promoting the city’s interest in creating a quality urban environment from all development projects.

2.15.1.A.1 Provide the planning commission with the staffing and other resources necessary to implement the Master Plan

- Who: Mayor’s office; City Council; CPC

- When: First five years

- Resources: General fund; federal funds

For many years, the Planning Commission office has been under-funded and under-staffed. The CPC has added staff with special expertise in areas such as transportation, urban design, and stormwater management. The CPC should also include planners with expertise in housing policy.

2.15.1.A.2 Create a system in which all stakeholders work with project proponents and the city to resolve differences and create successful development outcomes

- Who: CPC through the Neighborhood Participation Program

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time; Grants

Implement and provide resources for the participation process described in Chapter 15.

2.15.1.A.3 Create partnerships with the city’s educational and other institutions

- Who: CPC; educational institutions; medical institutions

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time; grants

Large institutions, especially the “eds and meds,” are critical to the city’s economy but they are also especially important as physical anchors to districts and neighborhoods. These institutions have a stake in the community because, unlike businesses, they are identified with the city and are not going to move anywhere. However, the edges of institutions, the impacts that their students or workers have on neighbors, and their plans for expansion, can create conflict and controversy. The CPC should cultivate relationships with the institutions and keep informed about their activities, perhaps by creation of a standing committee on institutional development. Many communities with higher education institutions ask for an annual report to the planning agency in a public hearing in response to a format created by the planning agency, and/or require the creation of an institutional master plan to be shared with the city. For large institutions, the Comprehensive Zoning Ordinance now requires institutional master plans.

2.15.1.A.4 Convene a cross-agency Master Plan Implementation Committee at least three times a year.

- Who: CPC

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

This committee could build on the existing Planning Advisory Committee made up of departmental representatives. The group should meet three times a year, with one of those meetings occurring during the time when the capital improvement program is being prepared. At these meetings, the agenda should be a report on implementation of Master Plan-related projects, exchange of information about ongoing or new projects, programs and funding sources, and discussion of how to align departmental priorities so that projects and programs can be reinforcing and produce the maximum benefit for the city.

2.15.1.B 1.B. Develop staffing expertise within the city regulatory and planning review agencies and departments of city government as to issues of design review

2.15.1.B.1 Require commissioners for HDLC, VCC, CPC and BZA to undergo training on matters of urban design

- Who: HDLC, VCC, CPC and BZA

- When: First five years

- Resources: Departmental budgets, commissioner time

2.15.2 Enhanced coordination between the CPC, planning staff, community development programs, and other entities that affect the city’s physical

development

2.15.2.A 2.A. Reorganize planning and zoning activities within city government to create a closer relationship between the CPC and implementing agencies

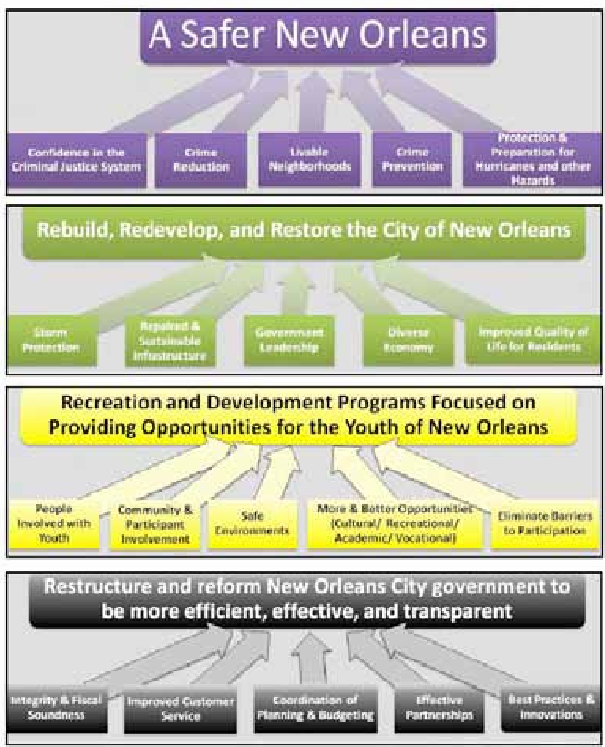

Source: City Of New Orleans 2009 ADOPTED BUDGET

A graphic from the 2009 City Budget. The document does not indicate how these goals were chosen.

A graphic from the 2009 City Budget. The document does not indicate how these goals were chosen.

The semi-autonomous status of the City Planning Commission, as provided in the City Charter, is not the way that most successful cities organize planning and land use regulation activities. (See for instance the document “Planning Department Organization: Selected Cities,” in the Appendix to this Plan.) This situation is yet another instance of the numerous ways in which authority and accountability

is fragmented in New Orleans local government. The Commission appoints the Executive Director, but that person is paid from funds controlled by the executive, and in fact the Commission has no funding of its own. The fact that the CPC is isolated from agencies that have funding to implement programs and projects results in a tendency to focus primarily on reacting to Budget project proposals and regulatory issues. It makes it more difficult to adopt a citywide planning perspective and to collaborate more effectively with NORA and agencies such as Code Enforcement and Safety and Permits in attacking blight and vacancy. In many cities, planning departments incorporate programs such as CDBG-funded housing rehabilitation and homeowner assistance; historic preservation programs and regulatory bodies; and brownfields redevelopment programs. (Examples of other organizational structures can be found in the Appendix.)

As OFICD is replaced with a Community Development department or agency, the role and relationships of the CPC within city government should be reviewed. Powerful options that would give planning more weight include combining Planning with Community Development or with the Redevelopment Authority.

2.15.2.A.1 Create an interagency group focusing on proactive planning

- Who: CPC; CAO; Senior leadership

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Planning Commission jobs and capacity were slashed and have only slowly been replaced. The Planning Commission was only tangentially involved in the post-storm recovery plans, despite the fact that the charter gives the Commission a specific role in post-disaster planning. In addition, during the recovery period, the Office of Recovery Management/OFICD and agencies working with OFICD, such as NORA, took on much of the proactive planning role that normally would be the province of the city’s planners.

Barring significant reorganization of City agencies (discussed below), the implementation of the Master Plan and further proactive planning will have to take place through collaboration of a variety of city departments and agencies. Planning Commission staff today are sometimes not informed about initiatives originating elsewhere in city government that have an impact on the physical development of the city—a situation that appears to be a common problem for other departments as well. For example, the graphic titled “A Safer New Orleans,” and reproduced here from the City’s 2009 budget document, does not seem to have been shared with other planning processes going on at the same time.

The City Planning Commission works with a Planning Advisory Committee made up of agency representatives, but this group is focused on responding to specific project proposals. In order to engage in cross-agency forward thinking, the Planning Commission should convene an interagency proactive planning committee made up of representatives of the CAO’s office and senior management with responsibility for forward thinking, not technical staff. The group should meet three times a year, with one of those meetings occurring during the time when the capital improvement program is being prepared. At these meetings, the agenda should be a report on implementation of Master Plan-related projects, exchange of information about ongoing or new projects, programs and funding sources, and discussion of medium- and long-term planning. During the course of the master plan process, it became evident that the CPC is often not aware of the existence of master plans and policies created by other departments, despite the CPC’s role in capital project planning.

2.15.2.A.2 Review the role and position of the CPC in relation to implementation agencies such as Community Development and NORA

- Who: CPC; Mayor’s Office

- When: Medium-term

- Resources: Staff time

The heightened importance of the CPC’s role on the CIP process makes greater consultation with CAO’s office more urgent. The CAO and the CPC need to agree on how to use the Master Plan effectively in the capital planning process. The CAO’s office should be involved in discussions about Master Plan certification of proposed CIP projects.

2.15.3 Consultation of the Master Plan in making city decisions at multiple levels

2.15.3.A 3.A. Make the Master Plan a living document

Because a Master Plan is much more than the Land Use element and the Future Land Use Map, it is important to create systems and procedures to ensure that it is used to guide decision-making in city government and that it is evaluated regularly to see if strategies are working and if it continues to reflect community goals. Individuals move in and out of city government and the day-to-day demands on the attention of elected officials and staff can push the plan into the background as a decision-making tool. Successful implementation of the New Orleans Master Plan will require coordinated activity from many municipal departments, from elected leaders, and from partners in the private and nonprofit sectors. Accordingly, the following measures are recommended.

2.15.3.A.1 Review the plan every five years, as required

- Who: CPC

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time; grants

The 2008 master plan charter amendment requires a mandatory five-year review of the plan: Mandatory Review. At least once every five years, but not more often than once per calendar year, and at any time in response to a disaster or other declared emergency, the Commission shall review the Master Plan and shall determine, after one or more public hearings, whether the plan requires amendment or comprehensive revision. If amendment or comprehensive revision is required, the Commission shall prepare and recommend amendments or comprehensive revisions and readopt the plan in accordance with the procedures of this section. The Commission shall hold at least one public meeting for each planning district or other designated neighborhood planning unit affected by amendments or revision in order to solicit the opinions of citizens that live or work in that district or planning unit; it shall also hold at least one public hearing to solicit the opinions of citizens from throughout the community. In addition, it shall comply with the requirements of any neighborhood participation program that the City, pursuant to Section 5-411, shall adopt by ordinance.

In the five-year review, the process should include a summary of progress made on implementing the Plan, unforeseen circumstances—both opportunities and obstacles—that affect implementation, and a review of the overall vision, goals and policies of the Plan. The public should then be asked to confirm, revise, remove or add to these aspects of the Plan.

2.15.3.A.2 Update the Master Plan more thoroughly at least every 20 years

- Who: City Council; CPC

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

Many communities update their comprehensive plans every ten years, but at a minimum, the Plan should be thoroughly updated at least every 20 years. This should include a major public participation process and detailed attention to every plan element.

2.15.3.A.3 Review progress on the Plan in an annual City Planning Commission meeting and an annual City Council meeting

- Who: City Council; CPC

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

Whether or not there are any amendments being proposed, a public review of how the City is using the Plan, the way Plan objectives have shaped decision-making, successes and obstacles to implementation, and new circumstances that may affect the Plan’s goals and principles will keep the Plan current as officials and the public are reminded of its contents.

2.15.3.A.4 Use the Plan annually in preparing and approving departmental work plans, and the City’s operational budget, as well as its capital improvement program and capital budget

- Who: Mayor’s office and agencies; CAO’s office and agencies

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

The city will be using the new Plan for capital improvement programming. A number of cities also use their master plans in the annual budget process and in development of departmental work plans. Among other things, this helps to ensure a certain level of understanding throughout city departments of what is in the Master Plan and how it is being implemented. A statement of how the work plan reflects the priorities of the Master Plan should be required.

2.15.3.A.5 Use the plan in preparing and approving One-Year and Five-Year HUD Consolidated Plan documents

- Who: OCD

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

The required plans for HUD formula grants should also be consistent with the Master Plan and a statement on how the work plan reflects the Master Plan should be required.

2.15.3.A.6 Make multiple Planning Commission staff members into the Commission’s experts on the Master Plan

- Who: CPC

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

Experienced planner in the CPC’s Comprehensive Planning Division should become the department expert on the Master Plan, so that the Commission can respond to questions and documentation issues rapidly. The Comprehensive Division is in charge of mandated reviews and updates of the plan.

2.15.3.A.7 Collaborate more closely with the CAO’s office on the CIP

- Who: CPC; CAO

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

2.15.3.A.8 Update the Master Plan more thoroughly at least every 20 years

- Who: CPC

- When: Long-term

- Resources: Staff time

2.15.4 Capital improvement plan and capital budget consistent with the Master Plan

2.15.4.A 4.A. Ensure capital improvement processes are linked to the Master Plan

The 2008 charter amendment requires that the city’s 5-year capital improvement program and annual capital budget be consistent with the goals, policies, and strategies in one or more of the Master Plan elements, but does not give any guidance on how consistency is to be measured.

The Master Plan sets forth a vision for New Orleans’ future, a set of goals, strategies, and action steps to implement the strategies and achieve the goals. As a citywide policy plan intended to give broad guidance for decision making over the next twenty years, it does not, in its current form, enumerate a large number of specific capital projects. Rather, the plan focuses on policy and organizational initiatives to more effectively achieve the goals, and it identifies the kinds of projects that are preferred, given the goals of the plan. As the Master Plan is reviewed and revised over the years, and as area/neighborhood plans are adopted as part of the plan, the Master Plan may include more specific project information. This will also depend on implementation of recommendations to make the city’s financial policies, plans and operations more transparent.

2.15.4.A.1 Further refine the system to certify that capital improvement projects and any other public projects are in compliance with the Master Plan

- Who: CPC

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

The Master Plan embraces a multitude of topics. By creating a system of compliance documents, the City will not only go through a thorough process of assuring consistency with the Master Plan, it will be able to demonstrate that process and that compliance to the public. This does not have to be excessively burdensome; it simply requires documentation that the Plan was consulted and the aspects of the plan deemed to provide compliance. Because the Master Plan is a policy plan, there are many general categories of goals, policies, and strategies under which a variety of capital projects would legitimately reside.

Compliance with the Master Plan does not mean that a specific type of capital project must be named in the plan. However, if the connection between the project and the plan is not obvious, it will be necessary to provide an explanation of how, for example, this project furthers a goal, carries out a policy, or is part of a strategy. These compliance documents should accompany the capital program when it goes to the Mayor’s office and the City Council, and, for accepted projects, should be put on the Planning Commission web site for public review.

As part of the CIP process, departments proposing capital projects must prepare a narrative explanation of how the project furthers or does not interfere with the goals, policies, and strategies of the Master Plan, and make available to the CPC any departmental master plans or other relevant documents, so that the CPC can evaluate how their plans fit into the city’s overall master plan framework. The CPC should collaborate more closely with the CAO’s office on the CIP. Capital projects are subject to the City’s stormwater management requirements and these are reviewed for incorporation of best practices. A subsidence vulnerability statement is also desirable, but may require additional data gathering and development of procedures.

2.15.4.A.2 Maintain the City Planning Commission as the entity that certifies compliance with the Master Plan

- Who: CPC

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

Once an agency creates a Master Plan compliance document for a project, Planning Commission staff should review it and prepare a consistency certification, if warranted. The CPC staff will provide the consistency certification to the CAO’s office before the capital improvement program is presented to the CPC. If the project is not certified, then the department can resubmit, if desired, or take the project out of the proposed capital program. The department can also appeal to the Mayor, who should then hear both sides before making a decision.

2.15.4.A.3 Through the zoning ordinance, evaluate large private projects for compliance with the Master Plan

- Who: CPC

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

Private projects are subject to the zoning ordinance, which should be consistent with the Master Plan in terms of a variety of issues, including neighborhood character and housing policy, transportation, green space, energy efficiency, resilience and stormwater management and so on.

2.15.4.A.4 Continue publishing regular reports on the progress of capital budget projects

- Who: CAO’s Office

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

Make information available on the City’s website.

2.15.5 Citywide system for government property maintenance and management

2.15.5.A 5.A. Plan for maintenance, repair and replacement of assets

Asset management involves taking care of the physical systems and structures (including, for example, streets, buildings, and trees) owned by the City and its agencies. In order to make the most cost-effective decisions while maximizing service, public managers need to know how much annual maintenance is needed, the service life of the asset, and how it can be calculated. Answers to these questions can drive decisions on whether and when to maintain, repair or replace assets. A number of software systems connected to GIS are available that are designed to keep track of the condition of assets and support decision making about maintenance and replacement.

The Government Finance Officers Association recommends the following steps for creating a system for capital maintenance and replacement.1

- Develop and maintain a complete inventory of all capital assets in a database (including GIS), including information such as location, dimensions, condition, maintenance history, replacement cost, operating cost, etc.

- Develop a policy for periodic evaluation of physical condition.

- Establish condition and functional performance standards.

- Develop financing policies for maintenance and replacement and consider earmarking fees or other revenue sources.

- Allocate sufficient funds in the capital program and the operating budget for routine maintenance, repair and replacement.

- Prepare an annual report on capital infrastructure including:

- Condition ratings for the city

- Condition ratings by asset class and other relevant factors

- Indirect condition costs (for example, events like water main breaks that indicate condition)

- Replacement life cycle by infrastructure type

- Year to year changes in net infrastructure asset value

- Actual expenditures and performance compared to budgeted expenditures and performance

- Report trends in spending and accomplishments in the CIP. New Orleans in recent decades has suffered from an inability to maintain many of its assets, often resulting in higher replacement costs. The hundreds of millions of federal dollars currently being invested in public assets in New Orleans do not yet have an asset management system attached to them. The City has commissioned a report on setting up an asset management system but has not implemented it.

2.15.5.A.1 Make it a very high priority to establish an asset management system

- Who: CAO’s office

- When: First five years

- Resources: General fund

With the huge investment in new facilities now underway in New Orleans, it would be tragic for the city to be left without the capacity to prioritize its resources for maintenance and upkeep. According to the CAO’s office, a study concluded that an asset management system would initially cost approximately $3 million. Training and staff activities to maintain the information database would be additional over time. However, asset management systems are known to save communities money over the long term, so the system would more than pay for itself eventually.

2.15.5.A.2 Create an interagency maintenance plan for stormwater management and green infrastructure assets

- Who: CAO, S&WB, Parks and Parkways, NORA, public park administrators

- When: First five years

- Resources: General fund, federal grants

Because best practices for stormwater management in a subsidence prone city like New Orleans dictate the use of landscape elements to retain water and allow for infiltration, it is important that these installations receive adequate maintenance. The City now requires private developers to demonstrate a financial commitment to operations and maintenance. The city can streamline and improve maintenance of green infrastructure installations on public land through coordinated standards, scheduling, training, contracting, etc. across departments. This entails:

- A centralized inventory of green infrastructure installations and comprehensive maintenance schedule.

- Determining the agency or agencies best suited to house green infrastructure maintenance technicians.

- Identifying a protocol for interagency cost-sharing if applicable.

- Assessing the potential for meeting operations and maintenance by contracting with the private sector.

- Identifying a certification credential and/or skills combination desired and sharing this information with area community colleges and workforce development agencies

2.15.6 Improved internal and external accountability

2.15.6.A 6.A. Make transparency and communications an integral part of government operations

2.15.6.A.1 Create a performance measurement system and information warehouse for city employees and to share with the public

- Who: CAO’s office

- When: First five years

- Resources: Grant for setup; general fund and federal funds for operation

A number of cities have instituted performance measurement systems throughout city government. The City has implemented performance measurement systems modeled in part on Washington’s CapStat system—seen in 2009 as the best model for both municipal performance accountability and information sharing and usable internally by the city to enhance performance as well as being made available to the public. (For more information on model performance measures and data systems, see Volume 3, Chapter 16.)

2.15.6.A.2 Continue to enhance the city’s E-government capacity

- Who: Mayor; CAO; ITI

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

The City has taken numerous steps to improve its E-government capacity. Applications are available online. The Property Viewer provides many layers of information. The One Stop App website allows citizens, property owners and developers to track permits and citations online. NoticeMe provides notice of public meetings. LAMA allows inter-departmental processing of applications and communications.

2.15.6.A.3 Provide effective and meaningful access to information about municipal activities

- Who: Mayor; CAO; ITI

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

The City is increasingly making available significant amounts of information about operations, facilities, staff, resources, and activities to the public over the internet.

(See Volume 3, Chapter 16 for more information.)

2.15.6.B 6.B. Focus on more consistent and effective enforcement of municipal laws and regulations

Throughout the Master Plan process, at every meeting, citizens called for more effective enforcement of city regulations and pointed to enforcement lapses as a reason to withhold confidence that implementation of the Master Plan could make a difference in the future. Enforcement and accountability should be priority values for creating a more livable and prosperous New Orleans.

2.15.6.B.1 Provide the tools, training and funding needed for effective enforcement of the City’s laws and regulations

- Who: Mayor; CAO; line enforcement agencies

- When: First five years

- Resources: General fund; grants; federal funds

Visible enforcement of city laws is critical to confidence in the city’s future. Certain kinds of enforcement actions can involve fees or fines, which then can fund the training and tools needed.

2.15.6.B.2 Improve the Neighborhood Engagement Office and the 311 system to report back to citizens on enforcement actions

- Who: Mayor; Office of Public Advocacy; 311

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

When citizens alert 311 to the need for enforcement, they should be offered the opportunity to receive a response from the relevant department within one month of the complaint. Resolution of the problem may not be possible within a month, but the response should provide information on what the city has done to investigate the problem, what steps are legally open to it, and what the city plans to do. Electronic forms are now available on the city website to make reporting easy. The 311 office should also be copied on any response and should keep a database with open complaints that require resolution. The system of “trouble tickets” common among many manufacturers may serve as a model. Municipal governments that have these systems find that citizens are very grateful to get a response and be informed—even if it means that they find out that resolution may require court action, or take longer than they would like. Responsiveness and communication are very much appreciated.

2.15.6.B.3 Give “customer training” to staff who deal with the public and make the quality of interactions with the public part of employee reviews

- Who: CAO’s office

- When: First five years

- Resources: Grants; Staff time

Regular training to enhance staff-public interactions can remind staff of how to deal with the public.

2.15.7 More tax revenue for the general fund and an improved fiscal situation

2.15.7.A 7.A. Seek opportunities to increase municipal revenues and resources for services, programs, and facilities over the long term

2.15.7.A.1 Recruit chain retail to serve New Orleans residents and increase the tax base

- Who: NORA; Economic Development, NOLABA; CPC; regulatory strategy

- When: First five years

- Resources: Staff time

Build on the opportunity site analyses in the Master Plan creating, as appropriate, market studies, limited incentives, and focused recruitment efforts.

2.15.7.A.2 Commission a study of how New Orleans can strengthen its fiscal position

- Who: Finance Department

- When: First five years

- Resources: General fund

The study should include:

- Analysis of collection of revenues and opportunities to increase collections.

- Potential cost-efficiencies in delivery of government services.

- Study of all licenses, permits, fees and fines to identify potential increased revenues, and new approaches to revenue. Some communities develop criteria that help explain why some services have fees attached to them and others do not. For example, recreational activities whose purpose is primarily to benefit the individual should be more fee based than recreational activities that have a clear social basis benefiting the entire community.

- Study of utility rates under the control of the City Council and whether incentives for conservation (and lower bills) could be tied to higher rates.

- Identification of potential state and federal funding opportunities for appropriate projects and the internal resources needed to access these opportunities in a cost-effective way.

- Implementation strategies taking account of political, state constitutional, constituency- building, legislative aspects of the various approaches.

2.15.7.A.3 Regularly review the fees generated by City departments to more fully offset the staff time and resources that are necessary to process and review applications

- Who: CAO

- When: Regularly

- Resources: Staff time