A Context

A

network of neighborhoods with high quality of life is one of the most important keys to a successful city. Enhancing the livability of all New Orleans neighborhoods, while preserving their unique character, is one of overarching goals of this Master Plan. It is critical to retaining the residents who have returned and invested in the city or who want to return—and to making sure that their children will be able to stay in New Orleans—and to attracting new residents to make the city their home, too. As jobs increasingly follow people in the st century, rather than the other way around, investing in a high quality of life is also an economic development strategy.

Although some neighborhoods in today’s New Orleans are doing well, others face substantial challenges stemming from both pre- and post-Hurricane Katrina conditions. Every neighborhood can benefit from enhanced attention to city services, infrastructure and amenities. Support for neighborhood success depends on working with neighborhood residents to tailor policies to ft the particular needs and challenges that face them.

There are many ways in which New Orleans neighborhoods of all types can be improved and proactive neighborhood planning consistent with this citywide Master Plan will be necessary. Piecemeal improvements will not make a truly significant difference until three fundamental steps are taken:

- A comprehensive and integrated approach to eliminating blight. While New Orleans had approximately 26,000 blighted properties before Hurricane Katrina, the aftermath of the storm and the unplanned resettlement patterns since the storm have resulted in a complex challenge of significant patchwork blight (some 59,000 addresses as of June 2009)1 throughout the flooded neighborhoods combined with pre-Hurricane Katrina disinvestment. Almost every neighborhood has pockets of blight that need attention. Because the scale of the problem is so great, the city needs a multi-faceted approach that combines traditional tools with innovative solutions.

- Reinvention of the City’s approach to housing. New Orleans needs to reinvent the way it thinks about housing, to serve long-time residents with deep roots in the city and to welcome returnees as well as newcomers who want to help create the New Orleans renaissance. A new housing policy, based on credible data and the advice of housing interests within the city, will guide decision makers in applying the City’s housing resources in the most effective way to build community and provide housing for households across the range of incomes in the city.

- Enhancing neighborhood commercial districts and residents’ access to retail and services.Strategic location of civic uses to anchor local commercial areas, recruitment of supermarkets to better serve residents, provision for neighborhood corner stores where residents desire them, support for small businesses and merchants, and public investment that promote walkability can enhance neighborhood commercial areas.

- Neighborhood-level plans and audits tailored to specifc areas. By working together in partnerships, government, neighborhoods, nonprofts and the private sector can be successful in enhancing New Orleans’ quality of life. A system of district planners is needed to coordinate with all stakeholders and get policies and plans in place on the neighborhood level.

1 Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, www.gnodc.org

I. Neighborhoods

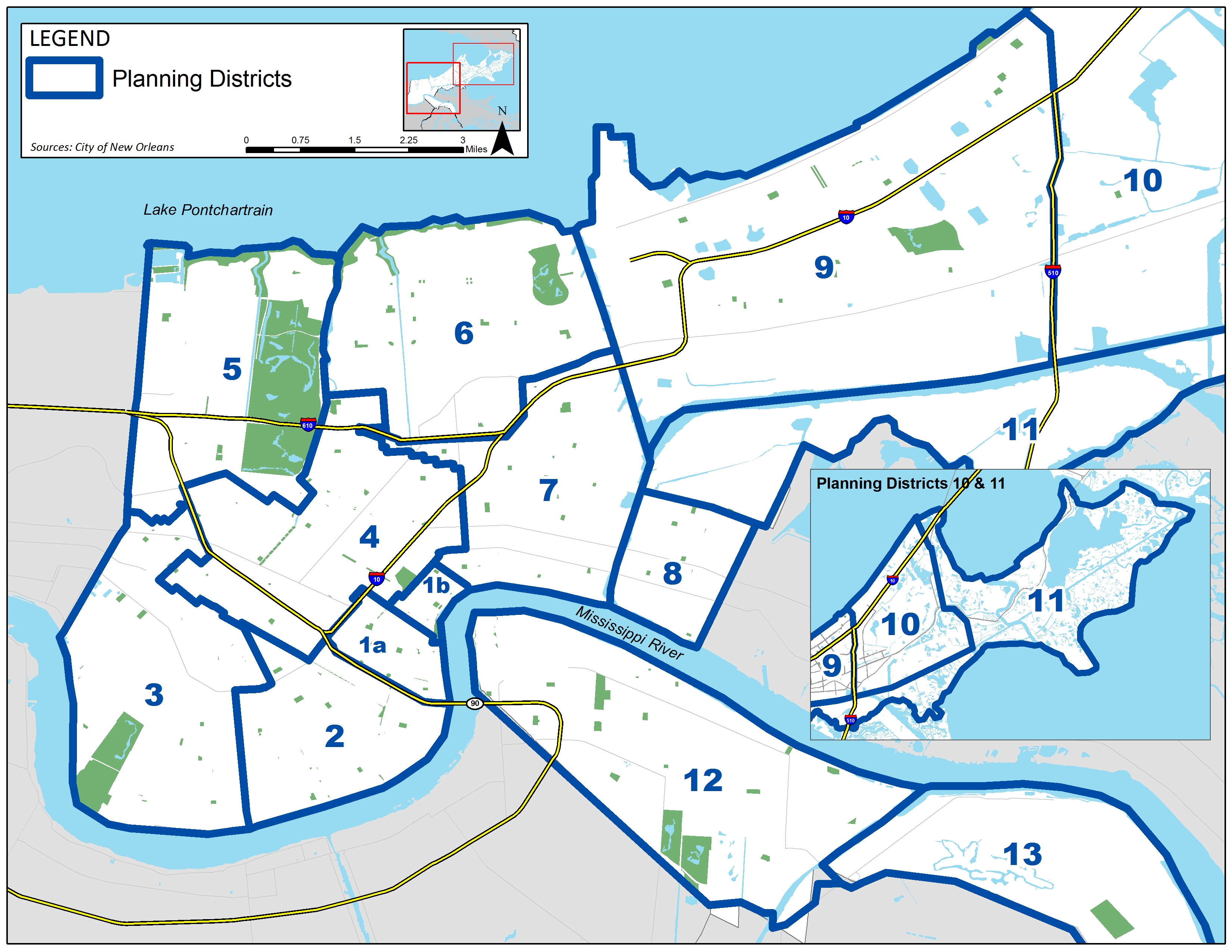

MAP 5.1: PLANNING DISTRICTS

New Orleans is famously a city of neighborhoods—crucibles of culture and cuisine and networks of family roots. In many parts of the city, neighborhood identifcation has become even stronger since Hurricane Katrina as people banded together to rebuild homes and communities. Almost every previous planning document examined for the master plan process and almost every master plan public meeting has made neighborhood protection, enhancement and revitalization the cornerstone of New Orleanians’ vision for the future.

How many neighborhoods does New Orleans have?

In the 1970s the City created a map of neighborhoods for planning purposes. Although that map still is used today, it now a historical document and does not consistently represent residents’ sense of neighborhood identity, which today may revolve around specifc neighborhood associations. During the Master Plan public process, discussions occasionally detoured into passionate exchanges about neighborhood names and boundaries. The local planning organization City-Works mapped over 200 community-based organizations throughout the city and found a plethora of neighborhood associations, some quite small and many with overlapping boundaries. Despite general identifcation with broad neighborhood areas, there are many parts of the city where neighborhood groups are emerging organically and with changing boundaries. In other parts of the city, particularly where security and improvement districts have been approved, or where there are identifable subdivisions, neighborhood boundaries are more settled. In this Master Plan, the City Planning Commission’s 13 planning districts have been used as a framework for the geography of the city. This Plan does not attempt to reorganize or redefne neighborhoods and accepts residents’ self-identifcation of their neighborhood location. As the Planning Commission implements this plan, it may prove valuable to revisit the neighborhood map, or keep the map to represent sub-areas of the planning districts because the neighborhood map areas have been used, especially since Hurricane Katrina, as statistical areas.

What makes a good neighborhood?

Good neighborhoods are the foundation of urban quality of life, and quality of life is the foundation of what makes cities successful in the 21st century. Businesses locate where people want to be, and good neighborhoods, along with great parks and a vibrant cultural life, are among the key attractions that any city can ofer. What makes a good neighborhood? On a basic level, good neighborhoods are safe, clean and healthy; supported by well-maintained and well-run public services; they are comfortable and attractive; and they provide good access and circulation internally and transportation choice to travel to and from the neighborhood. To many people, good city neighborhoods have the advantage of diversity, whether in the people who live there or the variety of uses and things to do. Ultimately, good neighborhoods are about people and connections. The physical and social organization of the neighborhood encourages people to get to know and trust one another. Over time, neighborhoods develop traditions.

Much of New Orleans’s cultural life has historically been connected to churches, synagogues and other religious institutions, many of which are embedded within residential neighborhoods and have served as catalysts for the formation of social bonds and communal identity. New Orleans has a large population of parochial and private school students. Entire neighborhoods bear the names of religious institutions. Future planning must be cognizant of these important cultural institutions and value the role they play in developing and preserving the cultural heritage of the city and in contributing to the well-being of its citizens and neighborhoods.

The preservation and encouragement of culture and tradition is an important aspect of neighborhood preservation in many parts of New Orleans. Before Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans was unusual among American cities in the high percentage of the population that had multi-generational roots in the city. Neighborhood churches and schools served as cornerstones of community life and physical landmarks and icons. On the neighborhood level, it was not uncommon for extended families to live close by one another. The storm tore many families from their neighborhood roots, and while many have returned, others are still awaiting the opportunity to return or have made the choice to live somewhere else for now. At the same time, New Orleans’ vibrant neighborhood life has been attracting new residents. Moreover, the mix of traditional and suburban-style neighborhoods was enriched with the emergence since the turn of the century of the Warehouse district and other new neighborhood options. All of these diferent types of neighborhoods not only can coexist but, by providing greater choice both to current residents and new residents moving from elsewhere, will strengthen New Orleans as an attractive and vibrant urban center.

A. NEIGHBORHOOD CHARACTER

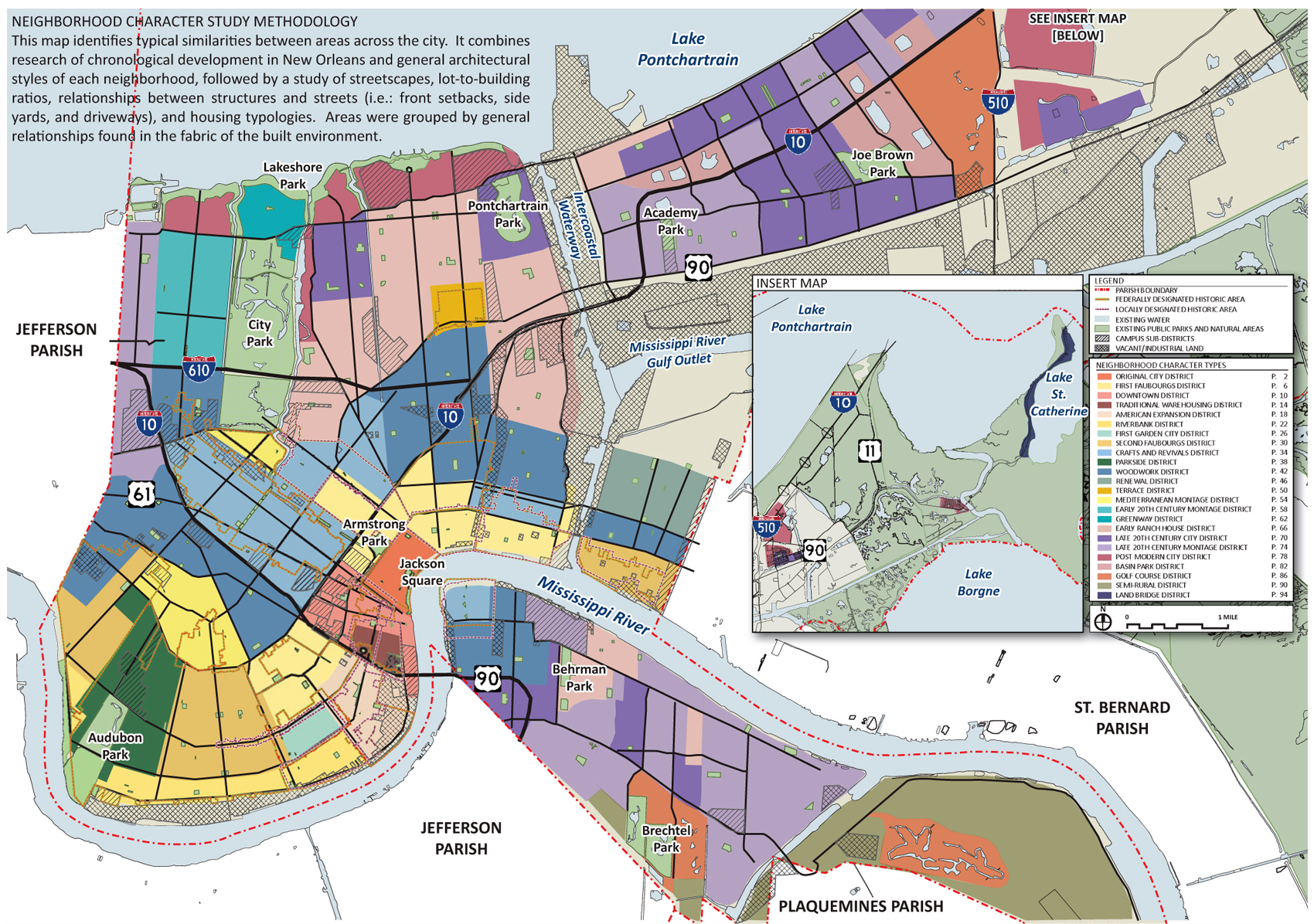

The physical character of New Orleans neighborhoods varies according to the period in which they were developed. Although there are many architectural and fine-grained diferences, a few strong discontinuities stand out. The fIrst came when the Louisiana Purchase brought Anglo-Americans into a Franco-Spanish city. In contrast to the closely-built creole buildings, Spanish-style balconies, interior courtyards, and vibrant commercial street life of the original port city, the mansions of the Garden district were set in large - lot gardens - like mini-plantations, becoming the “American Quarter” in contrast to the “French Quarter.” The second came after pumps allowed development of the “back swamp,” in the early 20th century. And the third came with development of suburban-style neighborhoods in the second half of the 20th century (the “postwar” era). According to the 2000 census, 100% of the city’s housing stock was built before 1960.

Jane Jacobs, who transformed her experience of living in her Greenwich Village neighborhood into a theory of urban life, argued for four basic principles of land use and physical development for cities: mixed uses, frequent streets, varied buildings, and concentration (or density). New Orleans has all of these, especially in the parts of the city built before World War II. The postwar, newer neighborhoods were built on the model of separated land uses and more homogeneous building types, and the potential of introducing some areas with a more mixed-use feel has been discussed in the newer parts of the city. The pre-Hurricane Katrina Renaissance Plan for New Orleans East, for example, planned for the redevelopment of Lake Forest Plaza mall into a mixed use “town center.”

MAP 5.2: NEIGHBORHOOD CHARACTER AREA STUDY

B. NEIGHBORHOOD TYPES

City planning departments typically divide neighborhoods into three categories:

- stable, successful neighborhoods that need support and protection;

- neighborhoods in transition, to better or worse conditions; and

- neighborhoods in need of revitalization. Before Hurricane Katrina, the 1999 Master Plan characterized neighborhoods as needing protection or revitalization, with the revitalization group focused in core city areas where most of the vacancy and blight was located. These general categories are suitable for New Orleans, but the impact of the food requires a more nuanced understanding of conditions in the city.

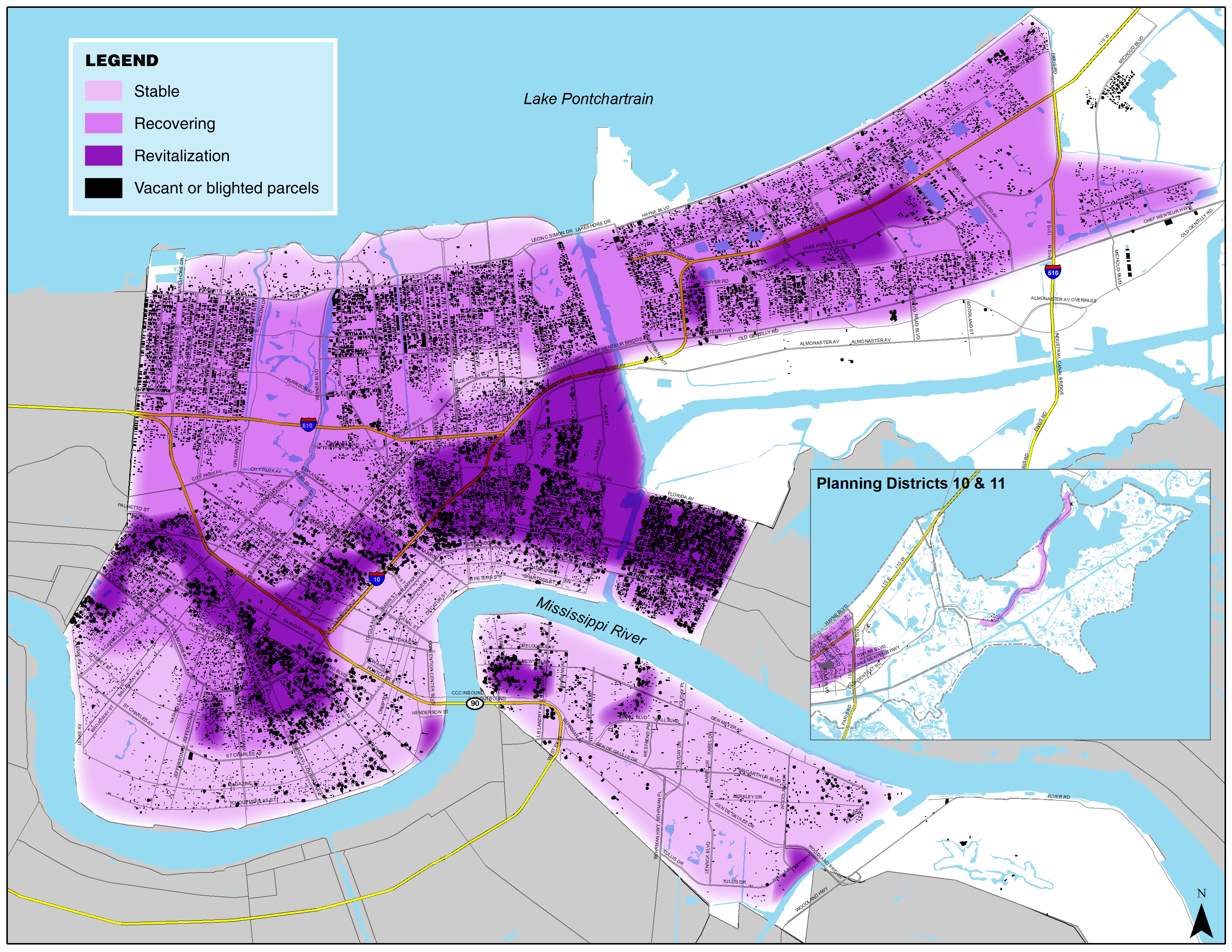

- Stable neighborhoods focus on protection, enhancement, and compatible infll. The higher-ground neighborhoods by the river and the lake and many parts of the West Bank did not food and the population in 2009 meets or even exceeds pre-storm levels. Residents in these neighborhoods are most concerned with assuring that their neighborhoods are safe, with wellmaintained public services and public spaces; that any infll development is compatible with the neighborhood; and that any development that occurs at the edges of the neighborhood is positive and does not have adverse impacts. There are small pockets of disinvestment in some of these neighborhoods. Many of these neighborhoods have strong neighborhood associations and some have security and improvement districts.

- Recovery neighborhoods focus on recovery, transitional land uses, and rebuilding. Before Hurricane Katrina, the neighborhoods that mostly were developed after 1950 in Districts 5, 6, 9 and 10—Lakeview, Gentilly, and New Orleans East—had some of the lowest vacancy rates in the city. Retail and large multifamily developments in New Orleans East suffered some disinvestment before the storm, but the East’s single and two-family neighborhoods were stable, middle-class communities. In 2009, while over 60% of the pre-storm population had returned in almost all areas, the recovery neighborhoods still had signifcant numbers of vacancies and lacked many of the civic and commercial services that they had before the storm. However, neighborhood associations are active, as are some security and improvement districts. These neighborhoods need more integrated and comprehensive policies of public action to accelerate recovery and leverage private investment.

These pages from the full Neighborhood Character Area Study describe buildings in the city’s Riverbank Districts.

These pages from the full Neighborhood Character Area Study describe buildings in the city’s Riverbank Districts.

- Revitalization neighborhoods focus on regeneration.Several neighborhoods had many challenges resulting from disinvestment and population loss before the storm and are still working on long-term revitalization. Four planning districts experienced the worst impacts of the 1980s recession, Districts Two (particularly Central City), Four, Seven (around downtown) and Eight (the Lower Ninth), and these areas, along with pockets in other districts, were still struggling in 2005. Some of them did not food, such as Riverside Algiers and Central City, while others, such as Hollygrove, St. Roch, and the Lower Ninth, suffered signifcant to disastrous fooding. The “dry” revitalization neighborhoods may be at an advantage during recovery because of their reduced risk of fooding compared to the “wet” neighborhoods. In these neighborhoods there are communitybased organizations that have been working on revitalization since before Hurricane Katrina and investment by the public sector and by nonprofts will continue to be critical.

Tables 5.1–5.3 provide data by planning district to compare pre- and post-Hurricane Katrina vacancy. The differential impact of Hurricane Katrina on the city’s neighborhoods is clear in Table 5.1. The table shows lots that had utility accounts in July 2005, before Hurricane Katrina, and did not have utility accounts in July 2008, three years after the storm: over 35,000 lots covering more than 5,000 acres. Fifty-six percent of these lots are in planning districts 5 (Lakeview), 6 (Gentilly), 8 (Holy Cross and Lower Ninth), and 9 (New Orleans East). The lots without accounts may contain an empty structure or may be entirely vacant.

MAP 5.3: NEIGHBORHOOD TYPES

Between October 2005 and the end of July 2008, 10,909 demolition permits were issued by the city.2 That number implies that many of the lots without utility accounts have an empty residential building on

them. Some property owners may be working on their properties or fully intending to reoccupy, but the majority of these lots are unlikely to be reoccupied in the short term. For comparison, planning district 12 on the West Bank, which did not food, has a much lower percentage of vacant properties. The table shows which planning districts contain the highest percentages of the total vacant lots, and which have the highest percentages in relation to the number of lots within the planning district. The least food-prone neighborhoods are largely back to full strength, with populations of 87%–107% of pre-Hurricane Katrina levels by September 2008. All planning districts had recovered at least 55% of their 2005 population by September 2008, except the Lower 9th Ward, at 19%. Before Hurricane Katrina, 39% of the population lived in the four planning districts least likely to food; now, 52% do.3

2 New Orleans Index Data Tables (January 2009), Table 17.

3 Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program and Greater New Orleans Community Data Center (GNOCDC), The New Orleans Index (August 2008 and January 2009).

C. NEIGHBORHOOD-SERVING BUSINESSES AND NEIGHBORHOOD COMMERCIAL DISTRICTS

The aftermath of Hurricane Katrina also had a diferential impact on neighborhood commercial areas. Commercial corridors along Magazine Street, Esplanade Avenue, and Maple Street—less afected by fooding—are thriving, while others in neighborhoods where resettlement has been slower continue to have vacancies. The recovery of small business has been hampered by capital shortages, lack of adequate insurance, and labor shortages. When participants in Master Plan district meetings were asked to place a dot on a map of the region to indicate where they did most of their shopping, it was clear that most residents do a substantial amount of their shopping in Jeferson Parish. (See sample map below.)

TABLE 5.1

|

Post- Hurricane Katrina Residential unoccupied lots* ( July 2008)

|

|

PLANNING DISTRICT

|

UNOCCUPIED RESIDENTIAL LOTS |

% OF TOTAL ESTIMATES RESIDENTIAL LOTS IN THE CITY

|

TOTAL ESTIMATED RESIDENTIAL LOTS (FROM GIS DATA)

|

% OF TOTAL DISTRICT LOTS THAT ARE OCCUPIED

|

COMMENTS

|

|

1

|

168

|

0.48%

|

5,090

|

3.30%

|

Includes all lots, not just residential

|

|

2

|

1,903

|

5.40%

|

12,255

|

15.53%

|

|

|

3

|

3,462

|

9.82%

|

21,662

|

15.98%

|

|

|

4

|

4,634

|

13.14%

|

16,043

|

28.88%

|

|

|

5

|

3,588

|

10.18%

|

14,999

|

23.92%

|

|

|

6

|

5,679

|

16.11%

|

18,090

|

31.39%

|

|

|

7

|

4,080

|

11.57%

|

13,241

|

30.81%

|

|

|

8

|

3,918

|

11.11%

|

7,699

|

50.89%

|

|

|

9

|

6,440

|

18.27%

|

23,145

|

27.82%

|

|

|

10

|

460

|

1.30%

|

2,340

|

19.66%

|

|

|

11

|

68

|

0.19%

|

966

|

7.04%

|

Includes all lots including marine commercial sites

|

|

12

|

845

|

2.40%

|

13,121

|

6.44%

|

|

|

13

|

9

|

0.03%

|

1,972

|

0.46%

|

Includes all residential lots, including small paper subdivisions that never had homes built

|

|

Citywide Total

|

35,254

|

|

150,623

|

23.41%

|

|

TABLE 5.2: SOURCE: NEW ORLEANS INDEX DATA TABLES(JANUARY 2009), TABLES 48 AND 49

|

UNOCCUPIED RESIDENTIAL ADDRESSES IN 2008 AND HOUSING UNITS IN 2000

|

|

PLANNING DISTRICT

|

UNOCCUPIED RESIDENTIAL ADDRESSES SEPT 2008

|

TOTAL ADDRESSES SEPT 2008

|

%

UNOCCUPIED SEPT 2008

|

CENSUS 2000 OCCUPIED HOUSING UNITS

|

CENSUS 2000 UNOCCUPIED HOUSING UNITS

|

ESTIMATED CENSUS 2000

% UNOCCUPIED HOUSING UNITS

|

|

1

|

618

|

5,478

|

11%

|

4,464

|

1,014

|

18.5%

|

|

2

|

6,027

|

25,826

|

23%

|

20,778

|

5,048

|

19.5%

|

|

3

|

4,493

|

31,522

|

14%

|

28,335

|

3,187

|

10.1%

|

|

4

|

11,837

|

32,031

|

37%

|

28,239

|

3,792

|

11.8%

|

|

5

|

5,597

|

13,479

|

42%

|

12,354

|

1,125

|

8.3%

|

|

6

|

8,268

|

18,401

|

45%

|

17,229

|

1,172

|

6.4%

|

|

7

|

7,902

|

18,680

|

42%

|

15,848

|

2,832

|

15.2%

|

|

8

|

6,763

|

8,244

|

82%

|

6,802

|

1,442

|

17.5%

|

|

9

|

12,715

|

29,220

|

44%

|

28,865

|

355

|

1.2%

|

|

10

|

1,800

|

4,143

|

43%

|

3,864

|

279

|

6.7%

|

|

11

|

825

|

1,661

|

50%

|

788

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

12

|

2,834

|

23,871

|

12%

|

20,310

|

3,561

|

14.9%

|

|

13

|

48

|

808

|

6%

|

375

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

Districts with N/A: these districts had new development in the 2000s before Hurricane Katrina, so the number of housing units in 2000 and the number of addresses in 2005 do not match as well as in other areas.

TABLE 5.3:

|

UNOCCUPIED LOTS BY ACREAGE AND PLANNING DISTRICT, JULY 2008

|

|

PLANNING DISTRICT

|

RESIDENTIAL ACRES UNOCCUPIED

|

TOTAL DISTRICT ACRES (ALL LOTS)

|

PERCENT OF TOTAL ACRES

|

|

1

|

46

|

1,067

|

4.33%

|

|

2

|

235

|

2,600

|

9.03%

|

|

3

|

413

|

4,858

|

8.49%

|

|

4

|

590

|

4,667

|

12.64%

|

|

5

|

560

|

4,658

|

12.02%

|

|

6

|

904

|

4,985

|

18.13%

|

|

7

|

497

|

3,721

|

13.36%

|

|

8

|

428

|

1,492

|

28.68%

|

|

9

|

1,230

|

13,073

|

9.41%

|

|

10

|

123

|

26,680

|

0.46%

|

|

11

|

38

|

37,280

|

0.10%

|

|

12

|

169

|

6,353

|

2.67%

|

|

13

|

7

|

4,445

|

0.16%

|

|

TOTAL

|

5,239

|

115,879

|

4.52%

|

Before the storm, New Orleans’ diverse neighborhoods had diferent types of retail districts: mixed-use commercial corridors with residential-scale retail, and auto-oriented corridors with low-density commercial uses, usually with suburban-style retail centers fronted by parking lots, and sometimes interspersed with residential uses. Moreover, many older New Orleans neighborhoods have small businesses at residential intersections, corner stores, or businesses interspersed with residences along neighborhood travel corridors.

Lack of neighborhood retail. The shortage of supermarkets is the most common resident complaint about lack of neighborhood retail. In July 2005, prior to Hurricane Katrina, there were 38 grocery stores for a population of 453,726, a ratio of one store per 12,000 residents. In May 2008, there were 19 grocery stores for a population of 326,875, a ratio of one store per 17,000 residents. This represents a 31% increase in residents per grocery store as of May 2008. The national average of residents per store is only 8,412—50% less than New Orleans. And, of course, the grocery stores are not distributed equally around the city. Large sections of New Orleans are currently underserved, including New Orleans East, Lower Ninth Ward, Upper Ninth Ward, Algiers, Gentilly and Lakeview.

MAP 5.4: GROCERY STORES

Corner stores—beloved institutions or nuisance businesses. Corner stores are found in many residential areas and, depending on the situation, are either beloved by residents or regarded as a source of nuisance or, in the worst cases, crime. In older neighborhoods, these stores, as well as restaurants and other commercial uses, often occupy residential scale buildings at one or more corners of intersections, for example, a typical situation in Marigny. As long as these businesses are well-managed and patronized by neighborhood residents, citizens are anxious to preserve them. However, they often do not wish to see conversion of more houses into nonresidential uses. In other neighborhoods, corner stores sell alcoholic beverages and little that serves neighborhood needs, sometimes becoming hot spots for drug dealing and other criminal activity.

Neighborhood Commercial Revitalization Efforts

A number of public and private entities are working now or are expected to work on neighborhood commercial district revitalization.

Main Street programs

There are six Main Street programs in New Orleans. Main Street programs

There are six Main Street Programs in New Orleans—all public- private initiatives. Four are state-designated Main Street Programs: Oak Street, Oretha Castle Haley Blvd, North Rampart Street, and St. Claude Avenue. These programs partner with the State of Louisiana, the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s National Main Street Center, and locally with the Regional Planning Commission, the Chamber of Commerce, and NewCorp, Inc., and others. Old Algiers Main Street Corporation and Freret Main Street are organized independently of the National Main Street Program, but follow the same four-point approach of design, promotion, organization and economic structuring to spur commercial revitalization in historic business districts. The Old Algiers Main Street Corporation partners with several corporate sponsors and elected officials, and Freret Main Street Program partners with the Neighborhood Housing Services of New Orleans.

In contrast to many Main Street programs in other cities, most of the New Orleans programs are not well-connected to city government (Old Algiers excepted). The state-designated programs have a six-year annual funding allocation of approximately $75,000 from the state, after which they are supposed to become self-supporting. These programs are currently in their third year. They receive limited guidance from the state program, but they are sometimes not consulted by the City when, for example, streetscape improvements are planned and constructed. City-Works, the planning nonproft, is working with the programs as a group to help them raise their profle and work together.

Cultural Products Districts

Nineteen state-designated Cultural Products Districts were established in 2008 that provide state tax credits to support the purchase and restoration of historic structures by artists and others in the districts, promote the establishment and expansion of art studios and galleries, and increase the sale of locally produced arts products. The art must be original, one-of-akind,visual, conceived and made by hand of the artist or under his/her direction and not intended for mass production. The New Orleans districts include: Old Algiers, Bayou Road, Lower Garden District, City Park/NOMA, Lower Ninth Ward, Oak Street, Magazine Street, Downtown Development District, Freret/Claiborne, Laftte Greenway, St. Claude Avenue, Vietnamese Village, Rampart/Basin, Gentilly/Pontchartrain Park, Lincoln Beach, Oretha Castle Haley, the French Quarter, South Broad, and Federal City/Tunisberg/Algiers Point.

At a Master Plan District Meeting in New orleans east,

many participants indicated that they often shop

in Jefferson Parish,rather than in New orleans.

The Stay local! campaign has published brochures

to promote local neighborhood businesses,

like this one for Mid-City.

The Stay Local! Campaign

Stay Local! is a project of the Urban Conservancy, which serves as a city wide resource to support and promote locally-owned and -operated businesses. This small grass-roots efort to support independent businesses has had a number of successes over the past several years, including:

- Launching a searchable Business Directory with over 1100 listings (www.staylocal.org)

- Publishing neighborhood guides and maps of locally owned and operated businesses

- Conducting mobile business summits to collaborate with local businesses on what is needed to stabilize, sustain, and grow businesses in various neighborhood commercial districts.

Neighborhood Markets

Numerous art markets and farmers’ markets have emerged in recent years, bringing consumers from throughout the metropolitan area back into the city’s neighborhood commercial districts.

- Art markets. The Freret Market, the Bywater Market, the Mid City Market and the Palmer Park Arts Market are held on rotating weekends so they do not compete with one another. In addition to selling art, each market hosts a variety of musical venues and food booths in order to create a day of entertainment as well as shopping.

- Farmers’ markets. Eight farmers’ markets include markets held daily, weekly, or monthly throughout the city. The daily French Market in the French Quarter is the oldest in the city. Weekly markets are held in New Orleans East (Vietnamese), Upper Ninth Ward and Downtown, Uptown, and Mid City. Monthly markets include the Sankofa Marketplace in the Lower Ninth Ward and the Harrison Market in Lakeview.

- Combined art and food markets. The Broad Street Bazaar, Renaissance Marketplace in New Orleans East, and Gentilly Fest Marketplace combine elements of both the art market and the farmers market. All of these markets broaden support for neighborhood commercial activities and build community cohesion across neighborhoods. The City owns the French Market, which is operated by an independent authority, the French Market Corporation. Historically, there were other city-owned markets in the neighborhoods. The city is currently restoring the St. Roch Market.

NORA Commercial Corridor Revitalization Initiative

The New Orleans Redevelopment Authority (NORA) signed a cooperative endeavor agreement with the City in October 2008 that includes $14.5 million for targeted neighborhood commercial corridor revitalization. NORA

will also continue to raise additional funds to promote commercial redevelopment. The corridors are:

- Tulane Avenue between South Claiborne Avenue and Carrollton Avenue

- South Claiborne Avenue between Earhart Boulevard and Napoleon Avenue

- Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard between Jackson Avenue and Pontchartrain Expressway•

- Gert Town/Carrollton Avenue between Jeff Davis Parkway, Earhart Boulevard,

- Washington Avenue, and Leonidas Street

- Bayou St. John & St. Bernard between Bayou St. John, Mirabeau Avenue, Paris Avenue and I-610

- Greater Tremé/Lafitte Greenway between Canal Street, North Rampart, St. Bernard Avenue, I-1-610, Wisner, and North Carrollton

- St. Claude Avenue between Elysian Fields and the Orleans Parish line.

- Pontchartrain Park/Gentilly Woods between Providence Place, Leon C. Simon, France Road, and Chef Menteur Highway

- New Orleans East – properties along the I-10 corridor and surrounding the former Lake Forest Plaza shopping center, including Lakeland and Methodist hospitals

- Chef Menteur Highway between Lurline Street and Wright Street

Assistance for Small Neighborhood Businesses

There is no central and complete resource on legal requirements and potential assistance for prospective or existing small businesses in the City. The website provides some valuable resources, several diferent guides to doing business—none of which is comprehensive—exist, and staf in diferent departments are often uninformed about requirements or resources from other departments. City representatives and business owners both agree that there is an urgent need to coordinate and bring together, under one roof, the diferent functions necessary to operate a business. The City recognizes that the existing application process is cumbersome and is working on a simplifed, defnitive process that can be used for all types of businesses (ranging from a Mardi Gras permit to a large renovation in an historic district). A committee of staf and business owners are working to identify hurdles that retailers face when applying for licenses and permits and rework the process.

Independent retailers and other small businesses often struggle to obtain capital under normal circumstances—a situation exacerbated by the global credit crunch prevailing at the time this Master Plan is being written. Assistance and incentive programs are also poorly marketed to small businesses. These programs include tax credits, training programs, tax exempt bonds, low interest loans, deferred property assessments, and property tax exemptions. (See Volume 3, Chapter 9 for a discussion of available incentives and programs.)

2. Existing programs and initiatives for neighborhood improvement and housing

A. DEPARTMENTS AND FUNDING

City resources for blight elimination, neighborhood improvement and housing programs are divided among several agencies and a variety of funding programs. The departments and authorities with these activities include the following:

- The Housing and Neighborhood Development Division corresponds to the typical community development department found in many cities that receive “entitlement” and grant funds from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). These entitlement funds are distributed according to a formula (and are accordingly sometimes called “formula funds”) based on population, income levels, and age of housing stock. In 2004, the division 1 had a staff of 115 and over $13 million in funding, the scale of entitlement funding typical before the storm. Funds were distributed through a competitive process to nonproft organizations and in some years not all funds were allocated. The 2009 adopted budget for the division 1 is $77 million ($ 65 M from HUD plus $12 M in other federal grants), which includes special federal funds for recovery. Although it appears that the 2009 staf of 109 would be administering a budget more than five times greater than in 2004, a signifcant portion of this funding is allocated to other agencies for implementation. A total of $30 million is available for rehabilitation programs, $20 million targeted at homeowners between 81–120% of Area Median Income (AMI, a number calculated annually by HUD) and $10 million for grants to elderly and disabled homeowners.

- The New Orleans Finance Authority was created in 1978 as a public trust by the City Council and its primary role has been to fnance frst time homebuyers through issuing mortgage revenue bonds. The City Council can also authorize it to provide tax-exempt bond fnancing for public facilities, facilities owned by non-profits, multi-family housing and all forms of community and economic development. The Finance Authority’s activities have been focused on the Housing Opportunity Zones designated by ORDA near the 17 Recovery Target Areas (see Volume 3, Chapter 3 for a map of these areas). A soft-second loan program for income-eligible

frst time homebuyers is underway and two other programs are awaiting approval as of mid-2009: a homebuyer program requiring somewhat greater investment by the buyer and open to a broader income group and a program called “Welcome Back Home Fund” that is designed to provide gap fnancing for homeowners whose insurance, frst mortgage, and Road Home payments have fallen short of what they need to renovate their homes since the storm. The Finance Authority is administering a $50 million soft second loan homeownership program targeted at low-and moderate income households.

- The Code Enforcement Department enforces the City’s housing code and receives funding from the general fund, fnes, and HUD entitlement funds.

- The Health Department enforces the City’s health code and receives funding from the general fund, HUD entitlement funds, and federal recovery funds.

- The Department of safety and permits enforces the building code and zoning code.

- The New Orleans Redevelopment Authority (NORA), an authority independent of city government, has signifcantly expanded activities in 2008, becoming the government’s chosen vehicle for a variety of neighborhood improvement and redevelopment activities. Its mission is to reduce blight, find opportunities and partners to build new and renovated housing, restore and build neighborhood commercial areas, and to use ,environmental and equitable best practices. Through a Cooperative Endeavor Agreement with the City, NORA is receiving signifcant federal recovery funding to take the lead on blight elimination and redevelopment. NORA is handling the disposition of the food-damaged properties sold to the state under the Road Home program known as the Louisiana Land Trust properties. With a consortium of community-based organizations, NORA has applied for $60 million in federal stimulus funds under the Neighborhood Stabilization Program.

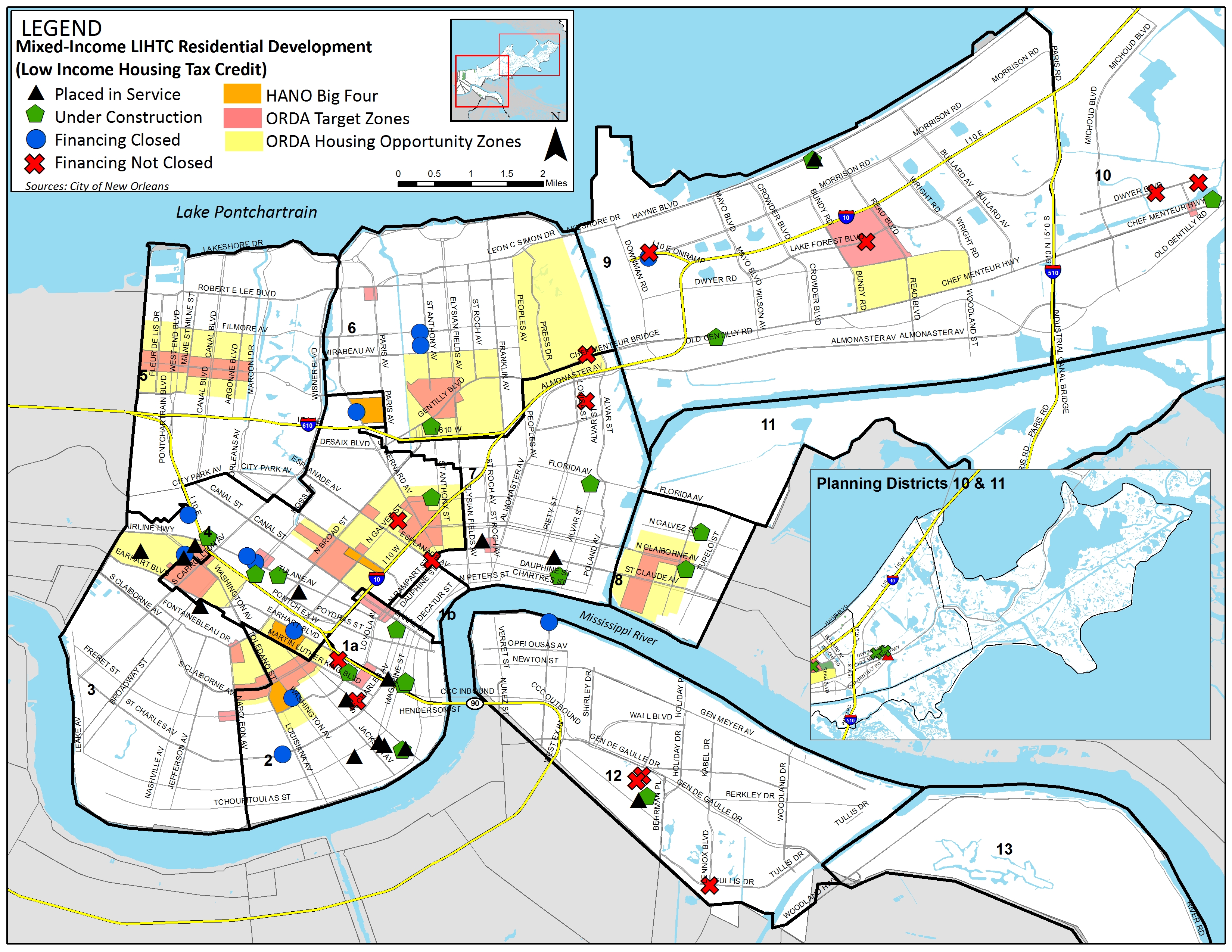

- The Housing Authority of New Orleans (HANO) is redeveloping former public housing sites on the community-building, mixed-use HOPE VI neighborhood model in order to deconcentrate poverty. HUD funding leverages private funding for these projects.

TABLE 5.4: SOURCE: CITY OF NEW ORLEANS 2009 BUDGET

| HUD ENTITLMENT FUND ALLOCATIONS FOR HOUSING AND NEIGBORHOODS (2009) |

|

| PROGRAM |

2009 AMOUNT |

| Rental rehabilitation |

$3.1 million |

| Housing preservation fund |

$2.0 million |

| Neighborhood stabilization program |

$2.3 million |

| HOME soft second loans for frst time homebuyer |

$5.6 million |

| Home downpayment assistance |

$0.9 million |

| Emergency home repair grants |

$3.2 million |

| Substantial rehab program |

$3.2 million |

| Lead hazard control |

$1.6 million |

| Neighborhood planning |

$0.4 million |

| TOTAL |

$22.3 million |

Funding sources for these agencies’ neighborhood and housing activities include:

- HUD entitlement funds: Community Development Block Grants (CDBG), Home Investment Partnerships (HOME) funds, Emergency Shelter Grants (for homeless persons), Housing Opportunities for People with AIDS (HOPWA). Formula funding from HUD is primarily allocated to a number of programs designed to rehabilitate existing housing—both rental and ownership—redevelop foreclosed, abandoned and blighted housing or vacant sites, and promote homeownership. The City receives these entitlement funds every year according to a formula, subject to continuation of federal law.

- Neighborhood Housing Improvement Funds (NHIF): NHIF was established by the City in 1992 to dedicate 1.25 mills of property tax for a period of 30 years (until 2022), to fund a comprehensive neighborhood housing improvement program and alleviate urban blight. This is a recurring source of funds. NHIF in 2009 has $3.5 M of which $455,000 is allocated to code enforcement/demolition, $520,000 to neighborhood stabilization, $750,000 to home ownership, and $1.5 M is reserved.

- State Emergency shelter grants: These grants supplement federal funding for homeless shelters and must be applied for.

- The louisiana Offce of Community Development in 2009 provided $189,526 in planning recovery funds. Funds are not automatically allocated.

- Temporary storm-related funding (excluding FEMA)

- Disaster CDbg funds (D-CDbg): The federal government allocated $411 million in long term recovery CDBG funds to New Orleans to complement FEMA funds dedicated to repairing storm damage. These funds are accessed through a state approval process and the frst project (this Master Plan) was not approved until May of 2008.

- Direct funding to property owners

- Road Home. Road Home covered uninsured losses for homeowners. In New Orleans, 43,500 homeowners had received funds as of January 2009, a high percentage of all homeowners impacted by Hurricane Katrina, and 90% of them chose to rebuild their homes.4 However, since the program did not cover damages exceeding pre-storm home value, over 80% of grant recipients did not receive suffcient funds to fully cover storm damage costs, with an average funding gap of $55,000. The funding gap was highest in some of the hardest-hit neighborhoods—$69,200 in New Orleans East and $75,400 in the Lower 9th Ward.5 Homeowners who chose not to rebuild sold over 4,600 properties to the state, which holds them as the Louisiana Land Trust properties. As noted earlier, NORA is working to put these properties back into use.

- Road Home Small Rental Property Program. Because this was originally a reimbursement program to assist owners of small (1- to 4-unit) rental buildings to rehabilitate storm-damaged buildings, it proved unworkable for many owners, who relied on the rental income to pay their mortgage and could not fnd fnancing to undertake the work. The program has been modifed to provide advance funding and as of May 2009, is expected to assist 7,600 housing units.

B. VACANCY AND BLIGHT ERADICATION

The most urgent and severe problem facing New Orleans neighborhoods is vacancy and blight. Blighted properties subject existing residents to health and safety hazards, depress property values and tax revenues, and deter new investment. The exact number of vacant and blighted properties in the city is not known, so proxy numbers—such as the number of lots without utility accounts after the storm mentioned above— are generally used to estimate the numbers. The Greater New Orleans Community Data Center analyzes the problem of vacancy and blight through the lens of mail delivery. By March 2009, there were 65,888 unoccupied addresses, of which approximately 59,000 were estimated to be on blighted or empty lots.6 In May 2009, 151,700 households were receiving mail, approximately 75% of the 203,457 that received mail in June 2005.7 If the estimated number of pre-Hurricane Katrina blighted properties is taken into account, the utility account lot data discussed earlier and the mail delivery data numbers are in the same order of magnitude, indicating the unprecedented conditions still facing New Orleans several years after the storm and flooding.

Before Hurricane Katrina, blight eradication programs in New Orleans produced limited benefits. Critics have cited overly broad goals, fragmented programs, and the lack of a comprehensive strategy, as well as inadequate funding, poor information tracking, barriers to the smooth acquisition and disposition of properties, and poor maintenance and cleanup of sites under City control as the source of poor results.8 These deficiencies in blight elimination activities were not unique to New Orleans—research has found that common barriers to effective code enforcement include inadequate legal powers and tools combined with a lack of coordination and a common action plan among multiple programs. In the post-storm environment, with an exponential increase in blight conditions, the inadequacy of the approach became clear.

Beginning in 2008 and with greater access to D-CDBG and other sources of funds in 2009, new approaches to blight remediation and application of much more funding were put in place in order to make a more visible difference in blight. Over $36 million in FEMA, Disaster-CDBG, regular CDBG, and city Neighborhood Housing Investment Fund dollars were allocated in the 2009 budget to blight reduction. This includes over $23 million for the cost of demolition, $5 million for “Clean & Lien” programs to stabilize properties after blight declarations, $3 million for cleaning up public nuisance vacant lots, $1.6 million for inspection and adjudication of commercial blight, and $3.8 million for staff and administration of the programs.9 Blight eradication and rehabilitation can be an expensive and painfully slow process, particularly in the jack-o-lantern conditions of flooded neighborhoods in the midst of recovery, where properties are acquired one at a time from individual owners.

An alternative to expropriation by streamlining code enforcement for blight or public nuisance. If the property owner does not take steps to come into compliance, the city will perform the necessary actions to ensure public health and safety and place a lien on the property to recoup the costs, making the property eligible for lien foreclosure.

MAP 5.6: VACANT RESIDENTIAL LOTS

Residential lots that became vacant or that have vacant buildings between July, 2005 and August, 2008, based on utility account data.

4 Data from the State of Louisiana’s Road Home website: www.road2la.org

5 Policylink, A Long Way Home: The State of Housing Recovery in Louisiana 2008 (August 2008).

6 Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, National Benchmarks for Blight, May 13, 2009, www.gnocdc.org/BenchmarksforBlight/, retrieved May 23, 2009.

7 May 2009, “Households actively receiving mail,” spreadsheet, GNOCDC website: www.gnocdc.org.

8 Bureau of Governmental Research (BGR), Mending the Urban Fabric: Blight in New Orleans, Part I (February 2008) and Part II (April 2008).

9 Joe Schilling, “Community Based Code Enforcement,”powerpoint presentation, American Planning Association National Conference, San Antonio, April 23, 2006, http://www.vacantproperties.org/resources/ppts/Schilling_APA_2006.pdf

Streamlined Code Enforcment

In 2008, a new city ordinance (Chapter 28) clarifying the code enforcement process was passed to provide an alternative to expropriation by streamlining code enforcement for blight or public nuisance. If the property owner does not take steps to come into compliance, the city will perform the necessary actions to ensure public health and safety and place a lien on the property to recoup the costs, making the property eligible for lien foreclosure.

- blight: A declaration of blight can be made if a property is chronically vacant; there are unsafe, unsanitary or unhealthy conditions; it is a free hazard; it lacks facilities or equipment required by the Housing Code; it is deemed “demolition by neglect” in the housing conservation district; it has a “substantial negative impact” on neighborhood health, safety or economic vitality; it is an abandoned, adjudicated or non-code compliant lot; there is vermin infestation. Properties determined to be blighted are turned over to the New Orleans Redevelopment Authority (NORA) for expropriation proceedings in civil court, which require payment of fair market value. Property owners can stop the case if they make repairs, sell the property or demolish it. Before expropriation, the City typically will seek an agreement with the owner to repair or sell the property.

- public nuisance: A property can be considered a public nuisance in the case of tall weeds; signifcant amount of trash or garbage; abandoned cars, appliances, debris, etc.; hazards to children because of unsecured conditions; conditions that could allow vermin infestations; objects that can hold standing water. Following determination of one or more violations, notifcation of the property owner and failure of the owner to eliminate the nuisance, the city can proceed to a hearing and a judgment with daily fnes of $100 to $500 if the condition is not corrected in 10 days. The city also has the right to enter the property to correct the condition and charge the owner.

expanded city capacity to

perform code enforcement

is an essential component of

continued revitalization.

The Department of Code Enforcement has received additional funding and staf and has adopted a system of “sweeps” through designated areas in order to create multi-block districts that can help stabilize surrounding area, rather than using limited resources on individual properties dispersed throughout the city. Other improvements include adoption of digital systems, and working closely with NORA and the Police Department to increase expropriations and reduce criminal activity in vacant properties. The City is focusing most of its anti-blight and code enforcement work on the City’s 17 designated recovery and/or housing opportunity zones, as well as several “stabilizing areas.” The purpose of focusing on these areas is to deploy signifcant enforcement actions in support of signifcant public investments slated for these areas. As the targets areas become more successful, private investment will be attracted and expand the recovery area into adjacent blocks. In the rest of the city, it will address only “urgent needs,” a decision that some have criticized, arguing that code enforcement in stable neighborhoods would leverage greater benefts in ease of returning properties to the market with higher tax values. Despite the increased funding, resources remain inadequate to the citywide challenge.

Although the Chapter 28 regulations made signifcant improvements, the problem of overlapping jurisdictions among various departments charged with enforcement of diferent codes (housing, building, zoning, health, demolition by neglect) remains a problem, as resolution of problems at an individual property can be delayed because there is not coordination of the enforcement activities of the various departments. Moreover, many code enforcement requests come through the City’s 311 information line, which has had inconsistent service. A reporting form is now available on the City website as well.

NORA blight reduction and redevelopment strategies

In 2008, $39 million in funds were allocated to NORA for blight eradication and redevelopment programs over the next few years. Although this is a much larger budget than the agency has ever had before, it is still insufcient given the scale of the problem in post-storm New Orleans. The redevelopment focus is on making a sufcient intervention in key areas to provide a critical mass that makes a visible diference, strengthens confdence, and attracts private investment. This is particularly the case in the recovery neighborhoods like Gentilly that were successful middle-class neighborhoods before the storm, and where the jack-o-lantern effect of dispersed resettlement can erode the investments that returned homeowners have already made.

NORA’s high-profile projects include redevelopment of Pontchartrain Park/Gentilly Woods (“Pontilly”) and an office building on O.C. Haley Boulevard . The first neighborhood redevelopment project to get underway is Pontilly. A development group that includes a well-known actor helps give the project visibility. The new houses will be at appropriate elevations, have 3 bedrooms and 2.5 baths, and be LEED- certified, making them extremely energy efficient. With subsidies, the prices of these state of the art single family houses will be the most attractive in the whole region for comparable units. NORA plans to build and occupy with its own offices a new building on O.C. Haley Boulevard as one catalyst for redevelopment of that important corridor.

TABLE 5.5:

| NORA BLIGHT REDUCTION AND REDEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS AND FUNDING |

| Program |

Description |

Amount |

Source |

| Clean and Lien |

Maintenance of properties found to pose a threat to public health and safety; placement of a lien to cover city costs, with lien foreclosure option. |

$5,000,000 |

D-CDBG |

| VA Land Acquisition and Redevelopment |

Acquisition and redevelopment of blighted, derelict and underutilized properties on the proposed site of the VA and LSU hospitals |

|

D-CDBG; UDAG |

| Pontilly Redevelopment and Acquisition |

Acquisition of residential and commercial property and redevelopment (including Gentilly Woods Shopping Center) |

$4,300,000 |

D-CDBG |

| Lake Forest Plaza Land Acquisition and Redevelopment |

Acquisition and redevelopment of land around the Lake Forest shopping center, including areas formerly a part of Lakeland and Methodist hospitals. |

$4,500,000 |

D-CDBG |

| South Claiborne Land Acquisition and Redevelopment |

Acquisition and redevelopment of blighted, derelict and underutilized properties in the area bounded by Napoleon, Broad, St Charles and Earhart Blvd. |

$4,500,000 |

D-CDBG |

| Additional Land Acquisition and Redevelopment |

Acquisition and redevelopment in areas including: Bayou District/St. Bernard; Greater Tremé/Lafitte Greenway Neighborhoods; St. Claude Avenue Corridor; O. C. Haley Avenue Corridor; Gert Town/Carrollton Avenue neighborhoods; Chef Menteur Highway. |

$10,000,000 |

D-CDBG |

|

|

Technical assistance for property owners with a homestead exemption to get the right of first refusal on adjacent properties owned by NORA. |

$250,000 |

D-CDBG |

|

|

Limited quick take authority except in the Lower 9th ward |

|

|

SOAP (Sale of Abandoned Property) city revolving account

|

|

|

Blight and Historic Property Rehab Loan Fund

|

|

To provide construction financing for small entrepreneur developers, contractors, nonprofits and others interested in redevelopment blighted properties and derelict historic properties. |

$2,000,000 |

D-CDBG |

|

Rehab and Construction Mitigation Study

|

|

|

Study to determine appropriate level of homeowner insurance pricing based on different risks and mitigation strategies.

|

|

|

D-CDBG |

| Commercial Appraisal Fund |

|

Appraisals to evaluate feasibility of acquisition.

|

|

|

D-CDBG |

|

Methodist Hospital Planning Study

|

|

|

Financial and physical feasibility study of former Methodist Hospital site and as-is appraisal.

|

|

$500,000 |

D-CDBG |

|

Property Inventory Database

|

|

|

Database to track status of all redevelopment properties, acquisition strategies and associated funding programs.

|

|

$375,000 |

D-CDBG |

| TOTAL |

|

$38,925,000 |

|

3. HOUSING

A. CONDITIONS AND MARKETS

If the key to New Orleans’ future lies in the quality of life of its diverse neighborhoods, each rich with its own history and unique housing characteristics, the restoration of its existing housing—and the thoughtful development of new infll housing that refects the diversity of each neighborhood—is critical. To prosper, New Orleans must provide safe and healthy housing for its diverse population with a wide range of incomes, from those who enjoy the economic benefts of higher paying jobs and rising incomes to the most vulnerable households (such as homeless or disabled persons and the working poor.) If New Orleans is to grow, it must provide housing appropriate for, and in demand by, all households—existing and new—who are attracted by the city’s unique opportunities and quality of life.

1. Housing in 2000

The 2000 census found that most of the 215,000 housing units in New Orleans were built before 1960 and were in older, small buildings (1–4 units). Forty-seven percent of households were homeowners—comparable to many other cities. The vast majority (70%) of the city’s rental units were in the small 1-4 unit buildings, and as many as half of these apartments were in substandard condition.10 The city’s 12.5% vacancy rate—over 20% in some neighborhoods—was one of the highest in the country, afecting 26,840 units.11 Housing costs were low in 2000, as was the city’s median household income at 83% of the state median and only 64% of the national median. Two-thirds of New Orleans households paid 30% or less of their household income for housing, the standard of afordability, with about 80% of owners paying less than 30% of their income towards housing expenses.12 Three quarter of the households that did pay more than 30% of their income were making under $20,000 per year.13 More than two-thirds of all rental units were afordable to low-income households.14 Most of these afordable units were low-cost, unsubsidized housing in privately-owned buildings, the 1–4 unit buildings mentioned earlier. Not only were these units an important housing resource for low and moderate income households, they were also an important source of income for small landlords.

10 City of New Orleans, Comprehensive Housing Accountability Strategy (CHAS) Report (1993), cited in New Orleans Draft Housing Element report

(circa 2002).

11 2000 Census data and New Orleans Draft Housing Element report (circa 2002).

2. Housing since Hurricane Katrina: a dynamic situation in flux

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, with 80% of the city flooded, 71% of the city’s entire housing stock was damaged, with major or severe damage to 105,000 units, or 56% of occupied buildings.15 As the rebuilding and recovery process has proceeded, the city’s housing market is in fux, with certain post-storm conditions apparently abating and the impacts of both the national market and expected new development yet to be fully understood.

Market rate housing

In the 2005–2008 period, the rebuilding process was creating newer and more expensive housing stock. In addition to the normal costs of rebuilding, labor was in short supply and key housing operating costs went up dramatically, most notably insurance and utilities. Rents rose 52% by 200816 and the median home value doubled compared to 2000, to $178,200.17

Homeowner housing

Before Hurricane Katrina, a signifcant portion of the owner-occupied housing stock was undermaintained—but it was also afordable, meaning low income households could pay 30% or less of their income for housing costs. After the storm, buyers of single family homes faced higher prices driven up by high insurance, utility, tax, and labor costs, with average home prices for the metro area climbing by nearly 50% since 2002, with the sharpest rate of increase in 2005–2007.18 The for-sale market softened in 2008 and 2009, echoing national trends, though prices still remained relatively high. In New Orleans, the average single family home sales price by December 2008 was $205,970, up from $189,610 the previous year, but the number of sales was down 26%. Across the city, some neighborhoods saw rising prices, while others experienced declining prices. For example, in Central City, City Park, and People/St. Bernard, prices were up 20%, while in Mid-City, Carrollton, the Garden District and the Lower Garden District, prices were down 6% to 8%. In New Orleans East, average prices were up in all neighborhoods. In the city as a whole, single-family permits for new construction in 2008 were 882, down from 1,026 in 2007.19

Market-rate homes are beyond the means of most low and moderate income households. City offcials estimate households need an income of at least 135% of median to aford an unsubsidized home,20 leaving homeownership out of reach for low and moderate and even many middle-income households. One estimate puts the afordable homeownership gap at 20,000 to 40,000 units for the New Orleans metro area.21 Since New Orleans has historically constituted roughly a third of its metro area, the gap for afordable for-sale homes in the city would likely be in the 6,000 to 12,000 unit range.

While most homeowners have received some fnancial assistance towards rebuilding their homes, they face multiple new fnancial challenges:

- Payment of mortgage and other costs for their damaged homes, as well as the cost of temporary housing, over protracted periods of time

- Funding gaps in rehabilitating their homes because insurance and grants did not fully cover the damages in most cases

- Dramatic increases in 0ther ongoing housing costs, for example, insurance, if it can be obtained at all, typically costs several times what it did before, utilities are up, and property taxes have increased.22

Many low-income pre-Hurricane Katrina homeowners lacked funds to adequately repair and maintain their homes. The Louisiana Housing Finance Agency estimates that some 7,000 existing homeowners may not to be able to keep their homes in this new high-cost environment.23

Rental housing

Though Road Home and other homeowner-oriented programs have been far from perfect, much more money flowed to assist in the rebuilding of owner-occupied homes than the small-scale rental buildings with low rents that were so important to the New Orleans rental market. While 51% of the existing rental stock sustained major damage24—as of mid-2009 public programs had been notably unsuccessful in bringing that rental stock back into livable condition, contributing to the city’s blight problem. Multifamily housing starts were down in 2008 compared to 2007.25 Rents in a sample of apartment complexes rose 15% between 2006 and 2007, and another 1.5% from 2007 to 2008.26 Apartment complexes tend to be concentrated in a few neighborhoods of the city, one of which is New Orleans East, which has limited public transportation connections to jobs in the hospitality or health care industries, for example. Low–income households looking for afordable housing near their work may double up with others in order to spend less money and time on transportation. There is insufcient data at this point about the housing choices and constraints faced by the many households of modest incomes whose workers are employed in the city’s service industries. Fewer renters than homeowners have returned to the city thus far, since there is simply nowhere for many of them to go.27

Housing markets

Housing markets

Between 1980 and 2009 New Orleans lost roughly 60,000 households (families or individuals who live in the city). By aggressively implementng actons identfed in this Master Plan, New Orleans could positon itself to atract these households back over the next 20 years and generate an influx of new households that could banish most blight and vacancy from the city’s neighborhoods.

What is New Orleans housing market like today?

A market study looking covering the next seven years—completed for this Master Plan-- indicates that more than 20,000 households have an interest in existng and new housing in New Orleans each year, including net new “market rate” demand for as many as 3,000 units of unsubsidized housing—if the City implements strategies for redeveloping blighted and vacant property, fxing infrastructure,diversifying the economy, and similar recommendatons contained in this plan. If the City fails to act, net new demand will likely only reach about half this number.

Over the next five to seven years. . .

|

Where people who want

housing in New Orleans

come from: |

Kinds of households that

will make up the housing

market: |

Anticipated demand for marketrate

housing: |

57%

ORLEANS PARISH

17%

SURROUNDING REGION

5%

REST OF LOUISIANA

21%

BALANCE Of THE U.S.

|

17%

EMPTY-NESTERS & RETIREES

32%

TRADITIONAL AND NON-TRADITIONAL FAMILIES

51%

YOUNGER SINGLES & COUPLES

|

WITH LIMITED ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND NO SIGNIFICANT INCREASE IN RESOLVING BLIGHT AND VACANCY

about 1,500 units per year

WITH EFFECTIVE ECONOMICDEVELOPMENT AND EXPANDED EFFORTS TO RESOLVE BLIGHT AND VACANCY

up to 3,750 units per year

|

Housing demand has shifted toward younger singles and couples—good news for New Orleans. These demographic groups help diversify economies and often seek out the older neighborhoods that have struggled since the 1980s. Younger households tend to prefer lofs, apartments and condominiums in renovated houses or new buildings, and smaller or atached single-family houses. Families with children and empty nesters tend to prefer atached and detached single-family houses. Looking at the entre market, interest in ownership should contnue to represent slightly less than half the market, while demand for high-quality, market-rate rental units (partcularly from better-of younger households and families with children) should increase substantally in comparison to recent decade.

As in virtually every U.S. city, demographic trends point to a growing populaton of homeowners in New Orleans who will want to sell single-family houses as they age. The supply of younger buyers will grow more slowly, and one statewide study suggests the two trends will produce an over-supply of single-family houses beginning about 2013. Rising interest in urban living works in favor of New Orleans’ neighborhoods, but the growing imbalance between sellers and buyers underscores the need to make improvements such as those identfed in this plan to enhance the city’s ability to compete for new residents.half this number.

Frequently asked questons

How have American housing markets changed over the past 30 years…and is New Orleans different? The number of younger and single households has increased dramatcally, to more than half the market in many cites, including New Orleans. While roughly three-quarters of households seeking housing in 1970 included children, today their proporton has shrunk to roughly one-quarter,and this trend holds true for New Orleans. Additonally,only one in ten younger households wanted to live in or close to downtown just a decade ago; that share has risen to one-third. The housing market in 2010 will be much more diverse in terms of the kinds of housing people seek, and more households will seek out urban neighborhoods—characteristcs that will likely hold true

over the 20 years of this plan.

Can every neighborhood in New Orleans compete in a growing market? Yes. In a market best described as “diverse,”households will seek new and old neighborhoods across the city. In additon to the factors noted above, providing a broad range of housing optons, including high-quality rental and ownership at a variety of price levels, will accelerate redevelopment.

Does every empty lot need to be redeveloped to refll neighborhoods? No. The Lot Next Door program, a general preference for larger units, replacement of some flooded multfamily complexes, and other infuences mean that some neighborhoods can come back with fewer households.

Why develop lofs and other new housing on “opportunity sites”? Won’t this new housing just steal demand from existng neighborhoods? No, the two don’t competewith each other. The housing proposed for opportunitysites appeals to households that want convenience, vibrancy, mixed-use, and new design. Inital market studies show near-term demand could fll a total of 5,000 to 6,000 units on these sites. While this represents only a small percentage of likely demand over 20 years, it accountsfor a signifcant slice of demand over five to seven years. Developing these sites to capture this potental market will support local businesses, expand the citywide tax base, and strengthen existng neighborhoods, making them more compettve

How do other cites make mixed-income housing successful? First, they emphasize high-quality design that enhances the character of “host” neighborhoods. Second, they mix market-rate, moderate, and lowerincome ,units, which keeps the market-rate component compettve under the market conditons that prevail in each neighborhood. Third, they involve local residents in planning the developments.

B. LONG-TERM HOUSING COSTS, HOUSING DEMAND, AND EMERGING MARKETS

At the time this plan is being written the longer-term trajectory of housing costs is difcult to project with confdence. Housing costs rose steeply in the two years after Hurricane Katrina, and some of the conditions driving those increases will likely remain in place, such as higher insurance costs. However, although displaced New Orleans residents continue to return, the pace of return is slowing, as those with the most resources have already come back. The ultimate impact of the 2008–2009 national credit and housing deflation crisis on New Orleans is likewise difcult to predict.

Future housing demand and the absorption of the many new rental units coming into the market in the next five years will depend on the city’s successful recovery, job creation, and perceived confdence in the city’s long-term resilience. The housing demand analysis discussed below must be understood in this context. It is not a prediction but a description of potential to be captured if the New Orleans’ recovery inspires confdence. New Orleans needs housing for a healthy mix of people of all income groups. Keeping up stable neighborhoods so that their existing housing remains attractive and valuable is as important as providing needed afordable housing. By the same token, providing new market rate housing choices also has a role in keeping New Orleans vital. A proper balance of traditional character and new choices will make the city welcoming to natives and newcomers alike.

Despite the unique challenges of analyzing housing market trends and likely future demand in the unstable and shifting environment of post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans, the city’s future is likely to be shaped by some of the same broad national trends impacting other large American cities. Nationally, two large demographic groups, the Baby Boomers (mostly in their 50s) and the Millennials (mostly in their 20s), are fueling a growing demand for urban living that should continue at least through the next decade. As many Boomers become empty-nesters and as the Millennials move out on their own for the frst time, both groups are discovering the convenience and pleasure of city living, particularly in neighborhoods that can ofer convenient transportation and shopping, cultural oferings, interesting street life, access to green space and nature, and other benefts. This back-to-the-city movement, combined with a trend towards smaller, 1–2 person households, is fueling strong demand for a broad range of urban apartments and homes. If New Orleans can fnd creative ways to meet the needs of these new would-be residents, their sheer numbers can help to fuel the city’s revitalization in important ways.A November 2008 analysis of residential market potential for New Orleans created for this master plan by Zimmerman/Volk Associates28 (See Volume 3, Appendix) determined that the potential market for new and existing housing units within the city is 23,200 households per year, including roughly 13,100 households moving within the city from one home to another, and roughly 10,100 new households moving to the city from elsewhere in the region or country.29 This is a 5 to 7 year projection based on the specific demographics of the New Orleans region and with the appropriate caveats about the national housing investment climate. This analysis focuses on market potential. It is not based on trends from the past but on the specifc demographic mix of this region.

Note that the households likely to move to or within New Orleans will do so if and only if the kind of housing they are looking for is available, a key issue, since the composition of this group of households as well as their housing preferences difer in important ways from those of the existing New Orleans population. The majority of these households would be looking for market-rate rental housing in multifamily building environments:

- 50% of demand from younger singles and couples

- 17% of demand from empty-nesters and retirees

- 45% buyers

- 55% renters

- 66% market rate

- 70% prefer multi-family (condos or apartments) in larger developments with amenities

- 20% prefer single family homes

- 10% prefer attached single family homes (townhouses and live-work units)

New Orleans in the past did not have many market-rate multifamily rental developments, though new mixed-income multifamily developments are beginning to become available. The success of the Warehouse

District and projects like the American Can adaptive reuse project in the 1990s and early 2000s were early indicators of this market.

These data do not mean that New Orleans cannot or should not attract families. They do, however, refect demographic realities that will afect the housing market until at least the 2020s. Some of the younger singles and couples of today will want to stay in New Orleans to raise their families, as long as they have confdence in the future of the city. Thus, the challenge facing New Orleans is to balance the needs of its existing residents to rebuild their cherished homes and neighborhoods, while at the same time creating new housing that will both attract and retain the next generations of residents, building homes for people across a broad range of ages, incomes, and lifestyles.

C. SUBSIDIZED HOUSING: A CHANGING LANDSCAPE

As noted earlier, before the storm, most affordable housing in New Orleans was provided by the private market but much of the housing stock was in poor condition. Housing is typically defined as “affordable” when a household pays no more than 30 percent of its income for housing-related costs. Housing costs for rental housing include rent and utility expenses. Housing costs for homeowners include mortgage payments, taxes and insurance. The “no more than 30% of income” standard is used by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) for its housing programs. Most states and localities have also adopted this affordability standard for their housing programs. There is some discussion nationally to include transportation costs as part of the affordability definition to support smart growth.

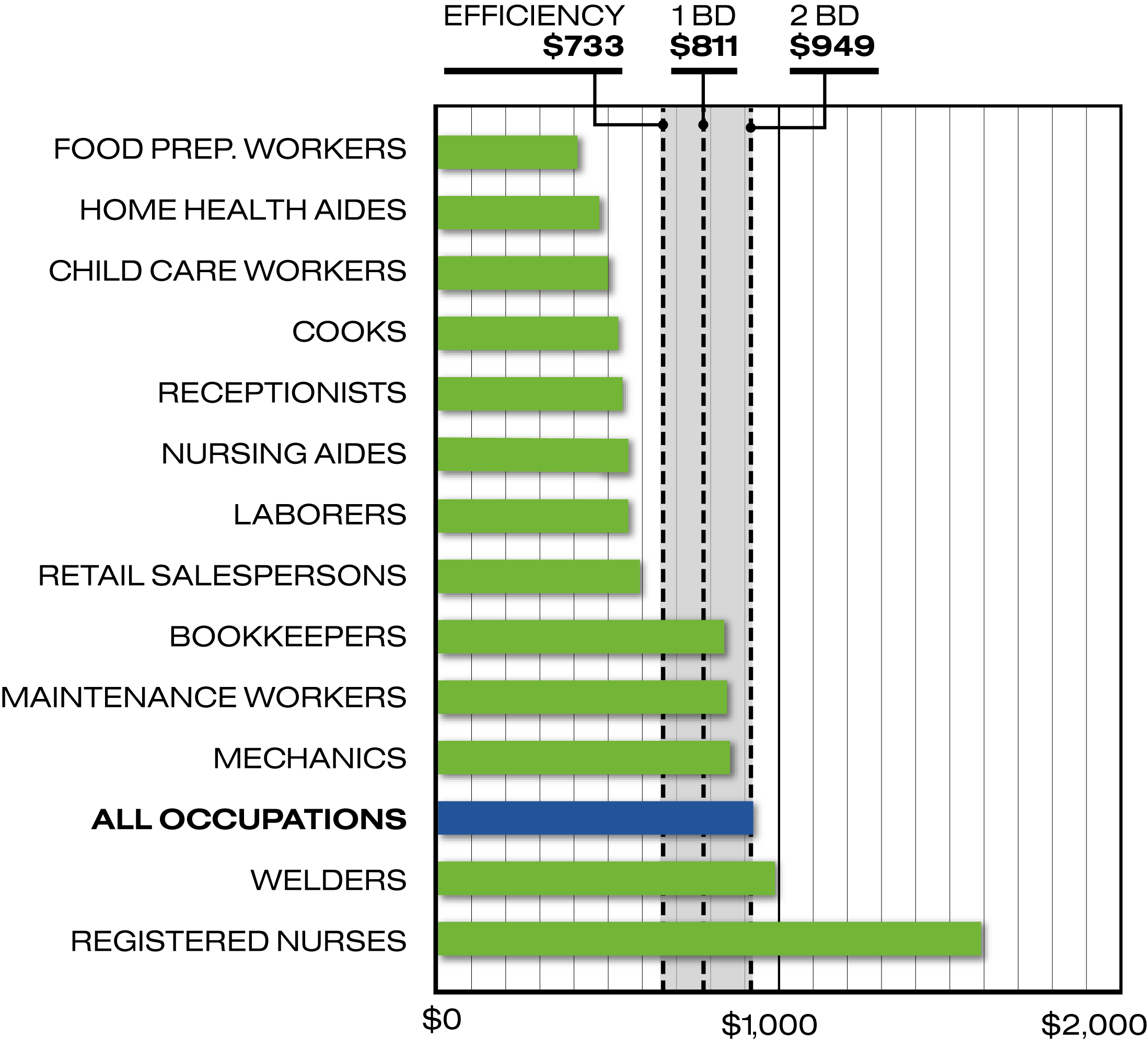

People with a wide range of incomes need affordable housing. They include persons on fixed incomes (the elderly and disabled), artists and musicians, working individuals and families, and homeless and special needs populations with supportive service needs—households who cannot find private housing that costs no more than 30% of their income. In New Orleans, this includes maintenance workers, bank tellers, police officers, fire fighters, retail salespersons, and construction laborers. The members of these households are productive members of the New Orleans’ workforce and are key to the city’s economic growth.

Government programs have been created to help people obtain decent, affordable homes. “Subsidized housing” is housing that is made available at below-market rates through the use of government subsidies. In most subsidized programs, households pay no more than 30% of their income, and the government pays the difference. Standard definitions are based on an “area median income” (AMI) which is calculated annually by HUD for metropolitan areas. The FY 2009 AMI for a family of four in the New Orleans metropolitan area is $59,800. Subsidies for rental housing are targeted to households with incomes at or below 80% of AMI, which is $47,850 for a family four. Most HUD programs target households below 80% AMI; the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program targets households below 60% AMI. In communities where the gap between housing costs and household incomes is particularly wide, state and local governments are also increasingly including households with incomes between 80% and 120% AMI for home buyer assistance.

TABLE 5.6: PH=Public Housing; PB8=Project Based Section 8; LIHTC=Low Income Housing Tax Credit units SOURCE: HANO

| HANO'S BIG FOUR MIXED-INCOME DEVELOPMENTS: TOTAL PLANNED UNITS |

| |

AFFORDABLE |

MARKET |

| |

PH* |

PB8* |

LIHTC* |

FOR-SALE |

SUBTOTAL |

RENTAL |

FOR-SALE |

SUBTOTAL |

TOTAL |

| Lafitte |

141 |

459 |

300 |

0 |

900 |

0 |

600 |

600 |

1,500 |

| BW Cooper |

209 |

0 |

238 |

40 |

487 |

213 |

40 |

253 |

740 |

| St. Bernard |

160 |

186 |

347 |

100 |

793 |

332 |

200 |

532 |

1,325 |

| CJ Peete |

193 |

0 |

144 |

50 |

387 |

123 |

0 |

123 |

510 |

| Total Units |

703 |

637 |

1,029 |

190 |

2,567 |

668 |

840 |

1,508 |

4,075 |

In addition to the large amount of low-cost housing in the New Orleans market before Hurricane Katrina (that was affordable to many low-income households without government assistance), there was a variety of subsidized housing in the city; public housing; Section 8 tenant-based housing vouchers, which subsidize market rents to private landlords; private housing built with Low-Income Housing Tax Credits; and HUD-assisted multifamily developments (including project-based Section 8 developments). About 10% of all city households lived in subsidized housing in 2005—10,300 in public or other federally subsidized housing, and another 9,100 living in private housing with Section 8 tenant based subsidies to reduce their rent burden.30 In addition to these sources of subsidy for rental housing, there are also government HOME funds to assist frst time homeowners with down payment or closing costs and housing rehabilitation programs, both typically targeted at households with incomes 80% or below AMI.

|

|

|

|

Single mother and daughter

|

Family of four

|

Single woman entering work force

|

Retired Couple

|

| WAITRESS |

CARPENTER

|

HOTEL DESK CLERK |

|

|

Annual income: $16,660

Available for monthly rent (30%): $416

2 bedroom Fair Market Rent: $978

Affordability Gap: $562

|

Annual income: $35,330

Available for monthly mortgage: $883

can affor a $110,000 home

Median home price: $231,000

Affordability Gap: $121,000

|

Annual income: $20,190

Available for monthly rent: $505

Efficient Fair Market Rent: $755

Affordability Gap: $250

|

Monthly Social Security check: $1,460

Available for monthly rent: $438

1 Bedroom Fair Market Rent: $755

Affordability Gap: $398

|

Public Housing and Section 8 Tenant-based Vouchers