A Context

1. Health Conditions and Health Care Access

According to the United Health Foundation, Louisiana ranked 50th in the nation in 2008 for overall health, and has been ranked either 49th or 50th since 1990. It ranks in the bottom five states on 10 of 22 measures of overall health, including a high prevalence of obesity, a high percentage of children in poverty, a high rate of uninsured population, a high incidence of infectious disease, a low rate of high school graduation, and a high rate of preventable hospitalization.1 A poll of New Orleans residents in August, 2009 revealed that only 9 percent of respondents thought that the quality and availability of health care in New Orleans was better than before Hurricane Katrina, while 62 percent thought that it was worse.2

Socioeconomic disparities in health outcomes are prevalent in New Orleans and pose an additional challenge. In spring 2008, uninsured New Orleans residents were statistically more likely to be low income,in fair or poor health, and/or African American. Nineteen percent of economically disadvantaged adults in New Orleans ranked their health as fair or poor, as compared to 9 percent of those with better economic status. Compared to those with private insurance, New Orleans residents covered by Medicare or Medicaid were more than three times as likely to report their health as fair or poor, and residents who were low-income, African-American, and/or elderly were significantly more likely to have severe and chronic health problems. Former patients of the Medical Center of Louisiana at New Orleans (MCLNO/Charity Hospital), New Orleans’ primary safety-net health care provider before Hurricane Katrina, were about 75% African-American and about 85% very low-income.3

TABLE 8.1:

| NUMBER OF PHYSICIANS PER RESIDENT IN THE NEW ORLEANS METROPOLITAN AREA PRE-HURRICANE KATRINA AND C.20086 |

| |

NUMBER OF MDS IN

THE GREATER NEW ORLEANS

METROPOLITAN AREA

|

RATE PER

100,000

POPULATION |

| Pre-Hurricane Katrina |

2,400 |

239 |

| c. August, 2008 |

1,800-2,000 |

256 |

| National Average |

— |

237 |

Hurricane Katrina significantly damaged New Orleans’ health care infrastructure, and resulted in a loss of both facilities and of personnel in the health care professions, including thousands of physicians about a thirdof whom were primary care providers.4 In 2008, a majority of New Orleanians surveyed continued to have difficulties accessing health care.5 However, as of 2008, the number of physicians per population for the New Orleans Metropolitan Area was greater than pre- Hurricane Katrina levels and greater than the national average, though area experts suggest that these numbers conceal a shortage of primary care physicians, psychiatrists, and certain subspecialties.6 Projected future population growth should also be considered when evaluating per-population healthcare statistics to ensure that this ratio keeps pace with area population growth. See Chapter 2 for a discussion of projected population growth in New Orleans.)

HOSPITALS

Ochsner Baptist Medical Center was

among the first hospitals to re-open after HUrricane Katrina.

Before Hurricane Katrina, the New Orleans metropolitan area was served by 78 state-licensed hospitals—including 23 in Orleans Parish—and had more hospital beds per population than the average across the country.8 Despite widespread hospital closures due to Hurricane Katrina, as of August, 2008, the total number of hospital beds per population in the New Orleans region had again surpassed the national average,9 and from the first to the third quarters of 2008, average hospital wait times showed a 24 percent decrease.10 By January 2009, there were 52 hospitals in operation throughout the region, including 13 in Orleans Parish.11 However, future population growth in the region will likely require additional capacity. One report estimates the projected additional demand in the region to be anywhere between around 760 to 1,400 beds by 2016, depending on a range of factors including health care reform and area population growth.12

TABLE 8.2:

NUMBER OF HOSPITAL BEDS PER RESIDENT IN THE

NEW ORLEANS METROPOLITAN AREA PRE-HURRICANE

KATRINA AND C.200812 |

| |

NUMBER OF STAFFED HOSPITAL BEDS IN THE GREATER NEW ORLEANS RATE PER 1,000 METROPOLITAN AREA

|

RATE PER

100,000

POPULATION |

| Pre-Hurricane Katrina |

4,000 |

4.5 |

| c. August, 2008 |

2,250 |

2.9 |

| National Average |

— |

2 |

As of 2009, the Southeastern Regional Veterans Administration (VA) Hospital and the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (LSU) in New Orleans both plan to opennew hospital facilities in the city as part of an enhanced medical district and biosciences corridor. It is expected that thecompletion of these plans would significantly increase the city’s ability to provide more inpatient and chronic care and increased emergency services. The 2009 Office of Recovery and Development Administration (ORDA) budget allocates $75 million for site preparation for the VA Hospital site.14 (See Chapter 9—Sustaining and Expanding New Orleans’ Economic Base for further discussion of the Medical District proposals.)

The Medical Center of Louisiana at New Orleans (MCLNO/Charity Hospital) was the region’s primary safety-net provider of care for residents without insurance as well as a major teaching facility before Hurricane Katrina. Through the LSU and Tulane Schools of Medicine, Charity Hospital trained an estimated 70 percent of the physician workforce in Louisiana,15 and treated over two-thirds of the region’s uninsured residents, although the volume of patient visits to Charity had been declining before Hurricane Katrina.16 As of June, 2009, Charity has not reopened, and LSU plans to eventually adapt its main hospital facility to another use.17

Methodist Hospital in New Orleans East has also not reopened as of 2009. The 2009 ORDA budget provides $30 million for land acquisition and planning for the

former Methodist Hospital site.18In the City of New Orleans, geographic areas lacking convenient access to hospitals and emergency care include New Orleans East, Gentilly, parts of the West Bank, and the Ninth Ward. The city’s emergency medical service (EMS) and other emergency response infrastructure are discussed in Chapter 10—Community Facilities and Infrastructure.

The Medical Center of Louisi-

The Medical Center of Louisi-

ana at New Orleans (MCLNO/

Charity Hospital) was the

region’s primary safety-net

provider of care for residents

without insurance before Hur-

IMAGES: St. Thimas Community Healty Center www.stthomashmc.org.

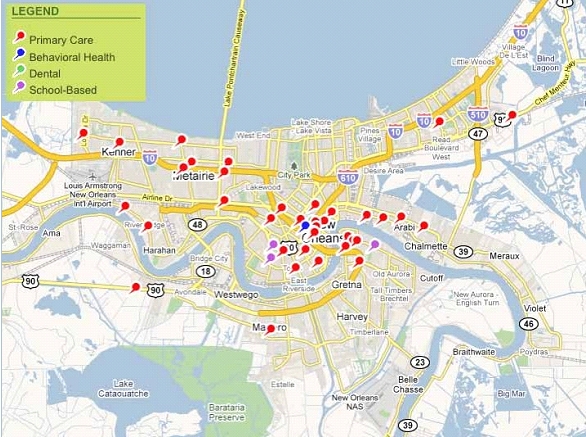

COMMUNITY CLINICS

In response to the dearth of major hospitals and other health care infrastructure post Hurricane Katrina, a substantial network of neighborhood-based primary care clinics developed in New Orleans and continues to expand. Community clinics are operated by a broad array of organizations—including academia, government, faithbased, and Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs)19—and offer services to patients with varying abilities to pay, including the indigent and uninsured. As of May, 2009, there were 58 community-based health care centers in the New Orleans metropolitan area, including:

- 35 primary health care clinics (18 in Orleans Parish)

- 15 behavioral health clinics

- 4 dental clinics

- 4 school-based health clinics.20

St. Thomas Community Health Center in the St. Thomas/Lower Garden District area of New Orleans is among the largest and most comprehensive primary care facilities serving both insured and uninsured patients in the New Orleans area.

New Orleans primary care facilities, c. September, 2009

IMAGE: www.gnocommunIty.org, September, 2009.

Additionally, the New Orleans Faith Health Alliance and Dillard University were each building a new clinic; both are expected to open in 2010. In March, 2009, the St. Thomas Community Health Center in New Orleans was one of seven community health centers in the state to receive a portion of the $8.6 million in federal stimulus funding for health care in Louisiana to expand the Center and provide services to more patients.21

As of March, 2009, 37 community clinics in the New Orleans region had been certified by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) as Patient-Centered Medical Homes. A Patient-Centered Medical Home is a health care setting that facilitates

partnerships between individual patients, and their personal physicians, and when appropriate, the patient’s family. Care is facilitated by registries, information technology, health information exchange and other means to ensure that patients get

the indicated care when and where they need and want it in a culturally and linguistically appropriate manner. (A Patient- Centered Medical Home is not a residence.) NCQA provides certification of Patient-Centered Medical Homes throughout the United States. The Medical Home model of care is a nationally recognized best practice that ensures coordination of services across the continuum of care, and has been a central tenet of health care reform initiatives in New Orleans and Louisiana since before Hurricane Katrina. The NCQA certification indicates that a provider meets certain standards of managed care, including demonstrating that patients have an ongoing relationship with a personal physician who is responsible for coordinating all of their health care needs. A grant administered by DHH and the Louisiana Public Health Institute (LPHI) provides funds for additional clinics to become certified by NCQA through 2010.

CHILDREN’S HEALTH

New Orleans has a high rate of poverty among children and a high rate of infant mortality—a common benchmark for children’s overall health. In 2008, 25 percent of families with children surveyed reported their child’s mental and emotional health was worse than before Hurricane Katrina, and 16 percent reported their child’s physical health was worse.22 A study comparing New Orleans children with blood lead before Katrina and ten years after showed a profound improvement. The blood lead reductions are associated with decreases in soil lead in the city. See the section on “Lead Poisoning” in the revised Chapter 12 – “Adapt to Thrive” Several programs are working to improve the health of children in New Orleans. They include:

- Nurse Family Partnership: For over 25 years, the Louisiana Office of Public Health and the Department of Health and Hospitals has run the Nurse Family Partnership, which improves pregnancy and early childhood health outcomes by matching nurses with low-income first-time mothers.23 The program has been shown to significantly improve pregnancy outcomes, child health and development, and family self-sufficiency, 24 and reaps an estimated $5.70 return on every dollar invested.25 Due to limited capacity, the program currently serves less than 50 percent of eligible participants.26

- Healthy Start New Orleans is a federally-funded program that provides prenatal and neonatal care for low-income women and their babies. It will receive $10 million in funding between 2009 and 2014 through the Department of Health and Human Services.

- Head Start And Early Head Start are national school readiness programs that provide free education, health, nutrition, and parent involvement services to low-income children from birth through preschool and their families.27 As of June 1, 2009, there were about 16 licensed child care facilities in New Orleans that offered Head Start programs.28 Many are operated by the nonprofit Total Community Action.29

- The Women, Infants and Children Food Program (WIC) provides supplemental food, health care referrals, and nutrition education for low-income expectant mothers and parents of children up to age 5. In 2007, 3,922 women and children in New Orleans benefitted from WIC.

- The Greater New Orleans School Kids Immunization Program has been successful in increasing immunization rates of New Orleans school children by offering free immunizations through schools. School Health Connection is a regional collaborative administered by LPHI that supports the expansion of school-based health centers in the New Orleans metropolitan area to improve the health of school-age children and their communities.30

MENTAL HEALTH

As of January, 2008, the rate of mental health conditions like depressive disorders and post traumatic stress disorder among New Orleans residents was several times the national average.31 In 2008, 31 percent of New Orleans residents surveyed reported having some mental health challenge, 15 percent reported having been diagnosed with a serious mental illness (three times the rate reported in 2006), and 17 percent reported having taken prescription medication for a mental health issue in the previous 6 months (more than twice the rate reported in 2006).32 However, the average number of poor mental health days for Louisiana residents was the 8th lowest in the nation in 2008 at 3 days per month.33

- United Health Foundation: http://www.americashealthrankings.org/2008/results.html#Table1. Retrieved February, 2009.

- Council for a Better Louisiana. “New Orleans Voter Poll on Post-Hurricane Katrina and Public Education Issues.” August 27, 2009. Available at: www.cabl.org.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. “New Orleans Three Years after the Storm: The Second Kaiser Post-Hurricane Katrina Survey, 2008.” Appendix: Chart- pack. August, 2008. Available at: www.kff.org.

- Williamson D. “Study shows Hurricane Katrina affected 20,000 physicians, up to 6,000 may have been displaced.” Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina; 2005. In DeSalvo, Karen, et al. “Health Care Infrastructure in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans:A Status Report.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. August, 2008. Volume 336, Number 2.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. “New Orleans Three Years after the Storm: The Second Kaiser Post-Hurricane Katrina Survey, 2008.” Appendix: Chart-pack. August, 2008. Available at: www.kff.org.

- DeSalvo, Karen, et al. “Health Care Infrastructure in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans: A Status Report.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. August, 2008. Volume 336, Number 2.

- Ibid.

- Brookings Institution and Greater New Orleans Community Data Center. “The New Orleans Index: Tracking the Recovery of New Orleans and the Metro Area.” January, 2009. www.gnocdc.org.

- DeSalvo, Karen, et al. “Health Care Infrastructure in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans: A Status Report.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. August, 2008. Volume 336, Number 2.

- City of New Orleans Budget Report, Third Quarter 2008. Available at: http://www.cityofno.com/pg-45-6.aspx. Retrieved June, 2009.

- Brookings Institution and Greater New Orleans Community Data Center. “The New Orleans Index: Tracking the Recovery of New Orleans and the Metro Area.” Appendix: Data Tables. January, 2009. www.gnocdc.org.

- Health Planning Source. “Medical Center of Louisiana—New Orleans Business Plan Review.” Prepared for the Downtown Development District of New Orleans.

- DeSalvo, Karen, et al. “Health Care Infrastructure in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans: A Status Report.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. August, 2008. Volume 336, Number 2.

- 2009 New Orleans Office of Recovery and Development Administration budget.

- DeSalvo, Karen, et al. “Health Care Infrastructure in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans: A Status Report.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. August, 2008. Volume 336, Number 2.

- Annual report. 2005 [cited May 15, 200S]. Available at: http://www.lsuhospitals.org/AnnualReportsl2005/2005_AR.pdf. In DeSalvo, Karen, et al. “Health Care Infrastructure in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans: A Status Report.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. August, 2008. Volume 336, Number 2.

- Health Planning Source. “Medical Center of Louisiana—New Orleans Business Plan Review.” Prepared for the Downtown Development District of New Orelans.

- 2009 New Orleans Office of Recovery and Development Administration budget.

- Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) are community-based organizations that provide care to all persons regardless of their ability to pay, and operate under supervision of the US Department of Health and Human Services.

- Louisiana Public Health Institute, May 2009.

- New Orleans City Business. “Louisiana Health Care to Get $8.6 Injection from Stimulus.” New Orleans City Business. March 3, 2009. http://www. neworleanscitybusiness.com/uptotheminute.cfm?recid=23401&userID=0&referer=dailyUpdate 22 Kaiser Family Foundation. “New Orleans Three Years after the Storm: The Second Kaiser Post-Hurricane Katrina Survey, 2008.” August, 2008.

- Nurse Family Partnership. Retrieved on November 21, 2008 at http://www.nursefamilypartnership.org/resources/files/PDF/Fact_Sheets/NFP_Nurses&Mothers.pdf.

- Louisiana Association of Nonprofit Organizations. “Community Solutions 2008-2009.” Available at: http://lano.org/AM/Template. cfm?Section=Community_Solutions_Institute. Retrieved July, 2009.

- Karoly, L; Kilburn, R; & Cannon, J. “Early Childhood Inverventions: Proven Results, Future Promise.” Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. 2005.

- “Health & Independence for All: A Strategic Plan.” A Working Draft United Way for the Greater New Orleans Area. December 8, 2008.

- National Head Start Association: http://www.nhsa.org/about_nhsa. Retrieve June, 2009.

- Greater New Orleans Community Data Center. www.gnocdc.org. Retrieved June, 2009.

- www.tca-nola.org.

- LPHI: http://lphi.org/home2/section/3-30-32-84/about-school-health-connection. Retrieved June, 2009.

- Kessler RC, Galea S, Jones RT, Parker HA. “Hurricane Katrina Community Advisory Group: Mental illness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina.” Bull World Health Org. 2006;84(12). Kaiser Family Foundation. “New Orleans Three Years after the Storm: The Second Kaiser Post-Hurricane Katrina Survey,

- 2008.” Appendix: Chart-pack. August, 2008

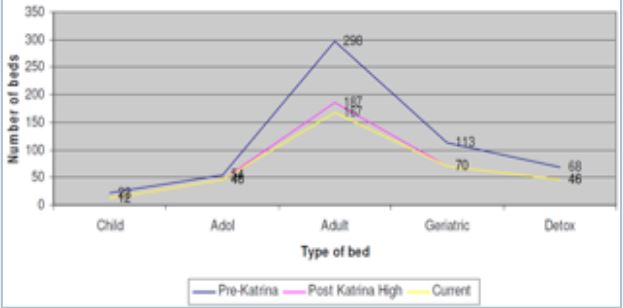

Inpatient Mental Health and Addiction Treatment

FIGURE 8.1:

Greater new Orleans inpatient psychiatric capacity

As of March, 2009, 168 of the hospital beds in New Orleans were inpatient psychiatric beds—less than half of the 364 available before Hurricane Katrina. There were 341 total psychiatric beds in the metropolitan region, as compared to 555 before Hurricane Katrina.34 A Kaiser Family foundation survey in 2008 noted that inpatient substance abuse treatment programs were in particularly high demand in New Orleans, especially for the uninsured and the homeless.35

The New Orleans adolescent Hospital (NOaH), the city’s only public mental health institution, will close in September, 2009. IMAGE: NOAH'S FRIEND'S: WWW.NOAHS-FRIENDS.ORG

In summer 2009, the State announced plans to close the inpatient mental health services at the New Orleans Adolescent Hospital (NOAH), the only public mental health institution in New Orleans. As of March, 2009, NOAH’s total inpatient capacity was 35 inpatient beds.36 Ninety-seven percent of children and adolescents and 93 percent of adults served by NOAH do not have insurance.37 Patients formerly served by NOAH will be served by Southeast Louisiana Hospital in Mandeville, LA after September, 2009. Several community groups in New Orleans have voiced opposition to this plan, and a law suit seeking to reverse the hospital consolidation plan was fled in 2009. Additionally, representatives of the business community have argued that businesses already suffer as a result of the city’s insuffcient mental health treatment capacity, and that increased mental health care is needed to make the city safe and secure for private investment.38Other hospitals in New Orleans that provide inpatientpsychiatric care (as of March, 2009) include:39

- Children’s Hospital (17 beds for adolescents)

- Psychiatric Pavilion (24 beds)

- Community Care Hospital (22 beds)

- University Hospital (20 detox beds)

- LSU Hospital—Calhoun Campus (38 beds)

- Louisiana Specialty (12 beds)

- Odyssey House (120 addiction treatment beds)

Outpatient Mental Health and Addiction Treatment

While adequate inpatient mental health care is essential to preventing crises and providing emergency mental health treatment in all communities, only about 7 percent of people who seek mental health care require hospitalization.40 National best practices in mental health treatment emphasize preventative and community-based outpatient care as signifcantly more efective and less expensive means of treating most mental health disorders than inpatient care.41

In New Orleans, there are several providers of outpatient mental health services. DHH operates the Louisiana Spirit program, a federally-funded crisis counseling service that is free to all Louisiana residents.42 Additionally, in 2010, DHH will fund and oversee the following outpatient mental health services and initiatives:

- Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams: ACT teams would provide ongoing outreach, monitoring, mental health treatment, medication management, substance abuse counseling, case management and social services for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance abuse who utilize both hospital and law enforcement resources. The ACT model has been proven to reduce institutional care and promote recovery in individuals with serious mental illness.43 As of June, 2009, there was already an advance waiting list for ACT services before they had begun to operate.44

- Supportive housing for people living with mental illnesses.

- Child and Adolescent Response Teams, which perform crisis stabilization for adolescents that has proven to decrease instances of hospitalization.

- NOAH outpatient and satellite clinics.

The New Orleans Metropolitan Human Service District (MHSD) provides outpatient treatment and supportive housing for persons living with addictive disorders, developmental disabilities, and mental illness through its Behavioral Health Centers.45 Additionally, more than 70 outpatient primary and behavioral health clinics in the New Orleans area provide mental health care in the metropolitan area regardless of ability to pay. They include:

- United Way Agencies

- VIALINK COPE LINE (provides referrals and emergency crisis counseling)

- Associated Catholic Charities of New orleans: recently expanded transitional housing for serious mentally ill residents

- Odyssey House: expansion plans include substance abuse and detox services

- Medical Center of New orleans (mClNo) at douglas, Jackson barracks, and Martin Behrman sites, st. thomas Community Health Center, Common Ground Health Clinic, eXCelth, daughters of Charity services, Tulane University Community Health Clinics, and Covenant House: working to integrate outpatient behavioral health services into existing primary care clinics.46

33 United Health Foundation: http://www.americashealthrankings.org/2008/states/la.html. Retrieved June, 2009.

34 Louisiana Public Health Institute Behavioral Health Action Network. March 26, 2009.

35 Kaiser Family Foundation. “New Orleans Three Years after the Storm: The Second Kaiser Post-Hurricane Katrina Survey, 2008.” August, 2008.

36 Ibid.

37 NOAH’s Friends: http://www.noahs-friends.org/default.asp.

38 Webster, Richard A. “City’s mental health care crisis impacts businesses.” New Orleans City Business. May 25, 2009. http://www.neworleanscitybusiness.com/viewFeature.cfm?recID=139039

Data courtesy Louisiana Public Health Institute Behavioral Health Action Network.

40 Mental Health America: http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/go/help/fnding-help/go/help/fnding-help/fnd-treatment/in-patient-care/inpatientcare-what-to-ask.

41 http://www.actassociation.org/actModel/

42 Louisiana Spirit: http://www.louisianaspirit.org/.

43 Lehman AF, Dixon L, Hoch JS, et al. “Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness.” Br J

Psychiatry 1999 Apr;174:346–52. Available at: http://ebmh.bmj.com/cgi/content/extract/2/4/128.

44 Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. http://www.dhh.louisiana.gov/publications.asp?ID=1&CID=9. Retrieved February, 2009.

45 Metropolitan Human Services District: http://www.mhsdla.org/home/.

46 Louisiana Public Health Institute Behavioral Health Action Network. March 26, 2009.

HOSPITALS

Ochsner Baptist Medical Center was

Ochsner Baptist Medical Center was

among the first hospitals to re-open after Hurricane katrina.

Before Hurricane Katrina, the New Orleans metropolitan area was served by 78 state-licensed hospitals—including 23 in Orleans Parish—and had more hospital beds per population than the average across the country.8 Despite widespread hospital closures due to Hurricane Katrina, as of August, 2008, the total number of hospital beds per population in the New Orleans region had again surpassed the national average,9 and from the first to the third quarters of 2008, average hospital wait times showed a 24 percent decrease.10 By January 2009, there were 52 hospitals in operation throughout the region, including 13 in Orleans Parish.11 However, future population growth in the region will likely require additional capacity. One report estimates the projected additional demand in the region to be anywhere between around 760 to 1,400 beds by 2016, depending on a range of factors including health care reform and area population growth.12

TABLE 8.2:

NUMBER OF HOSPITAL BEDS PER RESIDENT IN THE

NEW ORLEANS METROPOLITAN AREA PRE-HURRICANE

KATRINA AND C.200812 |

| |

NUMBER OF STAFFED HOSPITAL BEDS IN THE GREATER NEW ORLEANS RATE PER 1,000 METROPOLITAN AREA

|

RATE PER

100,000

POPULATION |

| Pre-Hurricane Katrina |

4,000 |

4.5 |

| c. August, 2008 |

2,250 |

2.9 |

| National Average |

— |

2 |

As of 2009, the Southeastern Regional Veterans Administration (VA) Hospital and the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (LSU) in New Orleans both plan to opennew hospital facilities in the city as part of an enhanced medical district and biosciences corridor. It is expected that thecompletion of these plans would significantly increase the city’s ability to provide more inpatient and chronic care and increased emergency services. The 2009 Office of Recovery and Development Administration (ORDA) budget allocates $75 million for site preparation for the VA Hospital site.14 (See Chapter 9—Sustaining and Expanding New Orleans’ Economic Base for further discussion of the Medical District proposals.)

The Medical Center of Louisiana at New Orleans (MCLNO/Charity Hospital) was the region’s primary safety-net provider of care for residents without insurance as well as a major teaching facility before Hurricane Katrina. Through the LSU and Tulane Schools of Medicine, Charity Hospital trained an estimated 70 percent of the physician workforce in Louisiana,15 and treated over two-thirds of the region’s uninsured residents, although the volume of patient visits to Charity had been declining before Hurricane Katrina.16 As of June, 2009, Charity has not reopened, and LSU plans to eventually adapt its main hospital facility to another use.17

Methodist Hospital in New Orleans East has also not reopened as of 2009. The 2009 ORDA budget provides $30 million for land acquisition and planning for the former Methodist Hospital site18

In the City of New Orleans, geographic areas lacking convenient access to hospitals and emergency care include New Orleans East, Gentilly, parts of the West Bank, and the Ninth Ward.

The city’s emergency medical service (EMS) and other emergency response infrastructure are discussed in Chapter 10—Community Facilities and Infrastructure.

The Medical Center of Louisi-

The Medical Center of Louisi-

ana at New Orleans (MCLNO/

Charity Hospital) was the

region’s primary safety-net

provider of care for residents

without insurance before

Hurricane katrina

- DeSalvo, Karen, et al. “Health Care Infrastructure in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans: A Status Report.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. August, 2008. Volume 336, Number 2.

- Ibid.

- Brookings Institution and Greater New Orleans Community Data Center. “The New Orleans Index: Tracking the Recovery of New Orleans and the Metro Area.” January, 2009. www.gnocdc.org.

- DeSalvo, Karen, et al. “Health Care Infrastructure in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans: A Status Report.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. August, 2008. Volume 336, Number 2.

- City of New Orleans Budget Report, Third Quarter 2008. Available at: http://www.cityofno.com/pg-45-6.aspx. Retrieved June, 2009.

- Brookings Institution and Greater New Orleans Community Data Center. “The New Orleans Index: Tracking the Recovery of New Orleans and the Metro Area.” Appendix: Data Tables. January, 2009. www.gnocdc.org.

- Health Planning Source. “Medical Center of Louisiana—New Orleans Business Plan Review.” Prepared for the Downtown Development District of New Orleans.

- DeSalvo, Karen, et al. “Health Care Infrastructure in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans: A Status Report.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. August, 2008. Volume 336, Number 2.

- 2009 New Orleans Office of Recovery and Development Administration budget.

-

DeSalvo, Karen, et al. “Health Care Infrastructure in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans: A Status Report.” The American Journal of the Medical

Sciences. August, 2008. Volume 336, Number 2.

-

Annual report. 2005 [cited May 15, 200S]. Available at: http://www.lsuhospitals.org/AnnualReportsl2005/2005_AR.pdf. In DeSalvo, Karen, et al.

“Health Care Infrastructure in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans: A Status Report.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. August,

2008. Volume 336, Number 2.

-

Health Planning Source. “Medical Center of Louisiana—New Orleans Business Plan Review.” Prepared for the Downtown Development District of New Orelans.

-

2009 New Orleans Offce of Recovery and Development Administration budget.

-

Federally Qualifed Health Centers (FQHCs) are community-based organizations that provide care to all persons regardless of their ability to pay, and operate under supervision of the US Department of Health and Human Services.

- Louisiana Public Health Institute, May 2009.

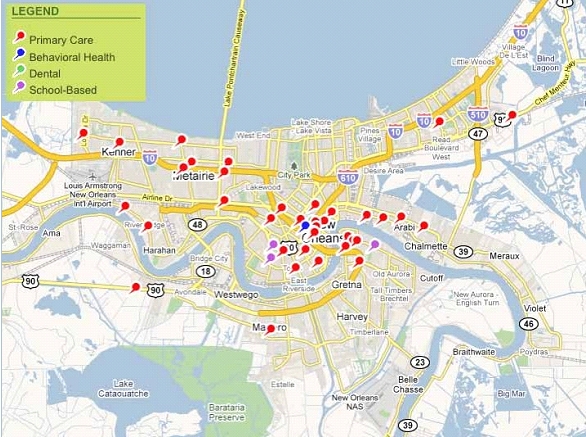

COMMUNITY CLINICS

In response to the dearth of major hospitals and other health care infrastructure post Hurricane Katrina, a substantial network of neighborhood-based primary care clinics developed in New Orleans and continues to expand. Community clinics are operated by a broad array of organizations—including academia, government, faithbased, and Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs)19—and offer services to patients with varying abilities to pay, including the indigent and uninsured. As of May, 2009, there were 58 community-based health care centers in the New Orleans metropolitan area, including:

- 35 primary health care clinics (18 in Orleans Parish)

- 15 behavioral health clinics

- 4 dental clinics

- 4 school-based health clinics.20

St. Thomas Community Health Center in the St. Thomas/Lower Garden District area of New Orleans is among the largest and most

St. Thomas Community Health Center in the St. Thomas/Lower Garden District area of New Orleans is among the largest and most

comprehensive primary care facilities serving both insured and uninsured patients in the New Orleans area.;

New Orleans primary care facilities, c. September, 2009 IMAGE: www.gnocommunIty.org, September, 2009.

Additionally, the New Orleans Faith Health Alliance and Dillard University were each building a new clinic; both are expected to open in 2010. In March, 2009, the St. Thomas Community Health Center in New Orleans was one of seven community health centers in the state to receive a portion of the $8.6 million in federal stimulus funding for health care in Louisiana to expand the Center and provide services to more patients.21

As of March, 2009, 37 community clinics in the New Orleans region had been certified by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) as Patient-Centered Medical Homes. A Patient-Centered Medical Home is a health care setting that facilitates

partnerships between individual patients, and their personal physicians, and when appropriate, the patient’s family. Care is facilitated by registries, information technology, health information exchange and other means to ensure that patients get

the indicated care when and where they need and want it in a culturally and linguistically appropriate manner. (A Patient- Centered Medical Home is not a residence.) NCQA provides certification of Patient-Centered Medical Homes throughout the United States. The Medical Home model of care is a nationally recognized best practice that ensures coordination of services across the continuum of care, and has been a central tenet of health care reform initiatives in New Orleans and Louisiana since before Hurricane Katrina. The NCQA certification indicates that a provider meets certain standards of managed care, including demonstrating that patients have an ongoing relationship with a personal physician who is responsible for coordinating all of their health care needs. A grant administered by DHH and the Louisiana Public Health Institute (LPHI) provides funds for additional clinics to become certified by NCQA through 2010.

15 DeSalvo, Karen, et al. “Health Care Infrastructure in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans: A Status Report.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. August, 2008. Volume 336, Number 2.

16 Annual report. 2005 [cited May 15, 200S]. Available at: http://www.lsuhospitals.org/AnnualReportsl2005/2005_AR.pdf. In DeSalvo, Karen, et al. “Health Care Infrastructure in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans: A Status Report.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. August, 2008. Volume 336, Number 2.

17 Health Planning Source. “Medical Center of Louisiana—New Orleans Business Plan Review.” Prepared for the Downtown Development District of New Orelans.

18 2009 New Orleans Office of Recovery and Development Administration budget.

19 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) are community-based organizations that provide care to all persons regardless of their ability to pay, and operate under supervision of the US Department of Health and Human Services.

20 Louisiana Public Health Institute, May 2009.

21 New Orleans City Business. “Louisiana Health Care to Get $8.6 Injection from Stimulus.” New Orleans City Business. March 3, 2009. http://www. neworleanscitybusiness.com/uptotheminute.cfm?recid=23401&userID=0&referer=dailyUpdate

CHILDREN’S HEALTH

New Orleans has a high rate of poverty among children and a high rate of infant mortality—a common benchmark for children’s overall health. In 2008, 25 percent of families with children surveyed reported their child’s mental and emotional health was worse than before Hurricane Katrina, and 16 percent reported their child’s physical health was worse.22 A study comparing New Orleans children with blood lead before Katrina and ten years after showed a profound improvement. The blood lead reductions are associated with decreases in soil lead in the city. See the section on “Lead Poisoning” in the revised Chapter 12 – “Adapt to Thrive” Several programs are working to improve the health of children in New Orleans. They include:

- Nurse Family Partnership: For over 25 years, the Louisiana Office of Public Health and the Department of Health and Hospitals has run the Nurse Family Partnership, which improves pregnancy and early childhood health outcomes by matching nurses with low-income first-time mothers.23 The program has been shown to significantly improve pregnancy outcomes, child health and development, and family self-sufficiency, 24 and reaps an estimated $5.70 return on every dollar invested.25 Due to limited capacity, the program currently serves less than 50 percent of eligible participants.26

- Healthy Start New Orleans is a federally-funded program that provides prenatal and neonatal care for low-income women and their babies. It will receive $10 million in funding between 2009 and 2014 through the Department of Health and Human Services.

- Head Start And Early Head Start are national school readiness programs that provide free education, health, nutrition, and parent involvement services to low-income children from birth through preschool and their families.27 As of June 1, 2009, there were about 16 licensed child care facilities in New Orleans that offered Head Start programs.28 Many are operated by the nonprofit Total Community Action.29

- The Women, Infants and Children Food Program (WIC) provides supplemental food, health care referrals, and nutrition education for low-income expectant mothers and parents of children up to age 5. In 2007, 3,922 women and children in New Orleans benefitted from WIC.

- The Greater New Orleans School Kids Immunization Program has been successful in increasing immunization rates of New Orleans school children by offering free immunizations through schools. School Health Connection is a regional collaborative administered by LPHI that supports the expansion of school-based health centers in the New Orleans metropolitan area to improve the health of school-age children and their communities.30

22 Kaiser Family Foundation. “New Orleans Three Years after the Storm: The Second Kaiser Post-Hurricane Katrina Survey, 2008.” August, 2008.

23 Nurse Family Partnership. Retrieved on November 21, 2008 at http://www.nursefamilypartnership.org/resources/files/PDF/Fact_Sheets/NFP_Nurses&Mothers.pdf.

24 Louisiana Association of Nonprofit Organizations. “Community Solutions 2008-2009.” Available at: http://lano.org/AM/Template. cfm?Section=Community_Solutions_Institute. Retrieved July, 2009.

25 Karoly, L; Kilburn, R; & Cannon, J. “Early Childhood Inverventions: Proven Results, Future Promise.” Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. 2005.

26 “Health & Independence for All: A Strategic Plan.” A Working Draft United Way for the Greater New Orleans Area. December 8, 2008.

27 National Head Start Association: http://www.nhsa.org/about_nhsa. Retrieve June, 2009.

28 Greater New Orleans Community Data Center. www.gnocdc.org. Retrieved June, 2009.

29 www.tca-nola.org.

30 LPHI: http://lphi.org/home2/section/3-30-32-84/about-school-health-connection. Retrieved June, 2009.

MENTAL HEALTH

As of January, 2008, the rate of mental health conditions like depressive disorders and post traumatic stress disorder among New Orleans residents was several times the national average.31 In 2008, 31 percent of New Orleans residents surveyed reported having some mental health challenge, 15 percent reported having been diagnosed with a serious mental illness (three times the rate reported in 2006), and 17 percent reported having taken prescription medication for a mental health issue in the previous 6 months (more than twice the rate reported in 2006).32 However, the average number of poor mental health days for Louisiana residents was the 8th lowest in the nation in 2008 at 3 days per month.33

31 Kessler RC, Galea S, Jones RT, Parker HA. “Hurricane Katrina Community Advisory Group: Mental illness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina.” Bull World Health Org. 2006;84(12). Kaiser Family Foundation. “New Orleans Three Years after the Storm: The Second Kaiser Post-Hurricane Katrina Survey,

32 2008.” Appendix: Chart-pack. August, 2008

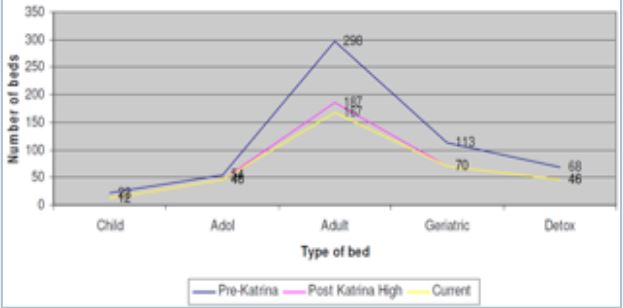

Inpatient Mental Health and Addiction Treatment

FIGURE 8.1:

| Greater new Orleans inpatient psychiatric capacity |

|

|

SOURCE: Louisiana public health institute behavioral health action network. March 26, 2009

|

| |

|

As of March, 2009, 168 of the hospital beds in New Orleans were inpatient psychiatric beds—less than half of the 364 available before Hurricane Katrina. There were 341 total psychiatric beds in the metropolitan region, as compared to 555 before Hurricane Katrina.34 A Kaiser Family foundation survey in 2008 noted that inpatient substance abuse treatment programs were in particularly high demand in New Orleans, especially for the uninsured and the homeless.35

The New Orleans adolescent Hospital (NOaH), the city’s only public mental health institution, will close in September, 2009. IMAGE: Noah's friends: www.noahs-friends.org

In summer 2009, the State announced plans to close the inpatient mental health services at the New Orleans Adolescent Hospital (NOAH), the only public mental health institution in New Orleans. As of March, 2009, NOAH’s total inpatient capacity was 35 inpatient beds.36 Ninety-seven percent of children and adolescents and 93 percent of adults served by NOAH do not have insurance.37 Patients formerly served by NOAH will be served by Southeast Louisiana Hospital in Mandeville, LA after September, 2009. Several community groups in New Orleans have voiced opposition to this plan, and a law suit seeking to reverse the hospital consolidation plan was fled in 2009. Additionally, representatives of the business community have argued that businesses already suffer as a result of the city’s insuffcient mental health treatment capacity, and that increased mental health care is needed to make the city safe and secure for private investment.38Other hospitals in New Orleans that provide inpatientpsychiatric care (as of March, 2009) include:39

- Children’s Hospital (17 beds for adolescents)

- Psychiatric Pavilion (24 beds)

- Community Care Hospital (22 beds)

- University Hospital (20 detox beds)

- LSU Hospital—Calhoun Campus (38 beds)

- Louisiana Specialty (12 beds)

- Odyssey House (120 addiction treatment beds)

Outpatient Mental Health and Addiction Treatment

While adequate inpatient mental health care is essential to preventing crises and providing emergency mental health treatment in all communities, only about 7 percent of people who seek mental health care require hospitalization.40 National best practices in mental health treatment emphasize preventative and community-based outpatient care as signifcantly more efective and less expensive means of treating most mental health disorders than inpatient care.41

In New Orleans, there are several providers of outpatient mental health services. DHH operates the Louisiana Spirit program, a federally-funded crisis counseling service that is free to all Louisiana residents.42 Additionally, in 2010, DHH will fund and oversee the following outpatient mental health services and initiatives:

- Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams: ACT teams would provide ongoing outreach, monitoring, mental health treatment, medication management, substance abuse counseling, case management and social services for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance abuse who utilize both hospital and law enforcement resources. The ACT model has been proven to reduce institutional care and promote recovery in individuals with serious mental illness.43 As of June, 2009, there was already an advance waiting list for ACT services before they had begun to operate.44

- Supportive housing for people living with mental illnesses.

- Child and Adolescent Response Teams, which perform crisis stabilization for adolescents that has proven to decrease instances of hospitalization.

- NOAH outpatient and satellite clinics.

The New Orleans Metropolitan Human Service District (MHSD) provides outpatient treatment and supportive housing for persons living with addictive disorders, developmental disabilities, and mental illness through its Behavioral Health Centers.45 Additionally, more than 70 outpatient primary and behavioral health clinics in the New Orleans area provide mental health care in the metropolitan area regardless of ability to pay. They include:

- United Way Agencies

- VIALINK COPE LINE (provides referrals and emergency crisis counseling)

- Associated Catholic Charities of New orleans: recently expanded transitional housing for serious mentally ill residents

- Odyssey House: expansion plans include substance abuse and detox services

- Medical Center of New orleans (mClNo) at douglas, Jackson barracks, and Martin Behrman sites, st. thomas Community Health Center, Common Ground Health Clinic, eXCelth, daughters of Charity services, tulane universityCommunity Health Clinics, and Covenant House: working to integrate outpatient behavioral health services into existing primary care clinics.46

33 United Health Foundation: http://www.americashealthrankings.org/2008/states/la.html. Retrieved June, 2009.

34 Louisiana Public Health Institute Behavioral Health Action Network. March 26, 2009.

35 Kaiser Family Foundation. “New Orleans Three Years after the Storm: The Second Kaiser Post-Hurricane Katrina Survey, 2008.” August, 2008.

36 Ibid.

37 NOAH’s Friends: http://www.noahs-friends.org/default.asp.

38 Webster, Richard A. “City’s mental health care crisis impacts businesses.” New Orleans City Business. May 25, 2009. http://www.neworleanscitybusiness.com/viewFeature.cfm?recID=139039

Data courtesy Louisiana Public Health Institute Behavioral Health Action Network.

40 Mental Health America: http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/go/help/fnding-help/go/help/fnding-help/fnd-treatment/in-patient-care/inpatientcare-what-to-ask.

41 http://www.actassociation.org/actModel/

42 Louisiana Spirit: http://www.louisianaspirit.org/.

43 Lehman AF, Dixon L, Hoch JS, et al. “Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness.” Br J

Psychiatry 1999 Apr;174:346–52. Available at: http://ebmh.bmj.com/cgi/content/extract/2/4/128.

44 Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. http://www.dhh.louisiana.gov/publications.asp?ID=1&CID=9. Retrieved February, 2009.

45 Metropolitan Human Services District: http://www.mhsdla.org/home/.

46 Louisiana Public Health Institute Behavioral Health Action Network. March 26, 2009.